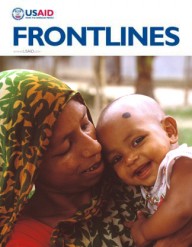

Left to right: Esther Maliga with daughter Jaminewa; Florence Lextion with daughter Alice Terewa; and Wilma Avowa, volunteer home health provider, at the Lanyi Primary Health Care Clinic, Mundri East County, Western Equatoria State, South Sudan.

Catharine McKaig, Jhpiego

Left to right: Esther Maliga with daughter Jaminewa; Florence Lextion with daughter Alice Terewa; and Wilma Avowa, volunteer home health provider, at the Lanyi Primary Health Care Clinic, Mundri East County, Western Equatoria State, South Sudan.

Catharine McKaig, Jhpiego

Left to right: Esther Maliga with daughter Jaminewa; Florence Lextion with daughter Alice Terewa; and Wilma Avowa, volunteer home health provider, at the Lanyi Primary Health Care Clinic, Mundri East County, Western Equatoria State, South Sudan.

Catharine McKaig, Jhpiego

Left to right: Esther Maliga with daughter Jaminewa; Florence Lextion with daughter Alice Terewa; and Wilma Avowa, volunteer home health provider, at the Lanyi Primary Health Care Clinic, Mundri East County, Western Equatoria State, South Sudan.

Catharine McKaig, Jhpiego

Lanyi, SOUTH SUDAN—When the gunshots started in Lanyi town last December, Wilma Avowa was grinding corn in preparation for dinner. She grabbed a few clothes and some food, and packed them in her bag. As she fled her home in this rural community five hours from South Sudan’s capital of Juba, she feared for her two pregnant neighbors, both of whom were due to deliver soon.

The two women, Esther Maliga, 19, and Florence Lextion, 24, were at home resting.

Lextion was lying on a mat on the floor when she heard the gunfire, her husband far away from the village tending to the family’s cattle. She got up quickly and packed a few clothes for the baby she knew was coming. Her plan to give birth in the local health facility was seemingly quashed by the civil unrest embroiling her nascent country, which became independent less than three years before.

She took the hands of her two children, 3 and 5 years old, and set off for the protection of the hillside about 2 kilometers away. Lextion moved as fast as she could, but had to stop several times to rest, hiding behind trees and lying flat on the ground with the children next to her.

By the time Lextion and her children reached the hillside, most of their neighbors were gathered there, including Avowa and Maliga. The women crowded under a rock overhang, which hid them from sight. They stayed there through the night and most of the next day. Lextion and Maliga both went into labor that afternoon.

Luckily for both women, Avowa was prepared. A volunteer home health promoter for the past 18 months, Avowa, 58, had stored in her bag three doses of misoprostol—a drug that helps prevent postpartum hemorrhage—along with an educational flip chart and two “Mama Kits,” the basic essentials needed to assist in a birth, including a sterile blade, a small plastic sheet, soap, gloves and ligatures.

Avowa had been trained to use misoprostol as part of a life-saving initiative supported by USAID. Postpartum hemorrhage is the leading cause of maternal deaths in most of the developing world. And South Sudan has the highest rate of maternal deaths in the world—2,054 per 100,000 live births, according to the U.N. Development Program.

“The good thing about miso, I could carry it with me when I ran,” says Avowa, recalling that December day and using a common nickname for the drug. Unlike other drugs that cause the contraction of the uterus and control bleeding, misoprostol does not require refrigeration—making it ideal to prevent bleeding after birth in South Sudan, where the vast majority of the country’s 11 million people have no access to electricity.

Avowa is among the 260 home health promoters who have been trained through the Mundri Relief and Development Association with USAID support. USAID and its implementing partner Jhpiego aim to ensure that the populations of South Sudan’s Western and Central Equatoria States—approximately 2 million people—have access to an integrated package of primary health care services, including prenatal and safe birth assistance. Other donors are focusing similar efforts in South Sudan’s other eight states at the request of the Ministry of Health.

More than 1,000 South Sudanese women have benefitted from this approach to saving lives since 2012, but no one could have imagined that this vital service would be provided in the bush.

South Sudan became independent on July 9, 2011, after a decades-long civil war between Sudan’s national government in Khartoum and the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, which sought autonomy for southern Sudan. On Dec. 15, 2013, fighting erupted among members of the armed forces in Juba. Violence pitting members of South Sudan’s two largest ethnic groups against each other quickly spread to neighborhoods in the capital and to Jonglei, Unity, Upper Nile and other states, eventually displacing approximately 1 million people.

“This program was started before the present crisis began, basically to meet the need of preventing postpartum hemorrhaging in a context where it is very difficult to reach health facilities, midwives are scarce and most women deliver at home,” said USAID Health Specialist Dr. Basilica Modi. “With the present crisis, the need for scaling up this particular intervention is even greater because, in the event that communities have to move, they normally move together with the health promoters who are part and parcel of their communities, so they will always be there with the pregnant women to provide them health education, counseling and misoprostol.”

Due Date

When the time came to deliver, Avowa laid out a small bed sheet on the long grass and used the contents of the Mama Kit to assist Maliga in giving birth. After a baby girl was delivered, Avowa gave Maliga the misoprostol to prevent excessive bleeding. Three hours later, she did the same for Lextion, who also gave birth to a healthy baby girl. Avowa says she helped the women move back under the rock overhang with their babies soon after they delivered to keep them safe.

Lextion says she wasn’t afraid while delivering daughter Alice Terewa, but “I wanted the baby to come quickly, so that if we needed to run later,” she could.

Maliga named her baby daughter Jaminewa. Both mothers say their daughters share a special bond, being born within hours of each other, in such difficult circumstances, and with the support of Avowa.

In spite of the conflict that erupted in South Sudan in December 2013, community midwives and volunteer home health promoters supported by USAID, including Avowa, have carried on their work—visiting pregnant women in their homes, helping them prepare a birth plan, and educating them on how to self-administer misoprostol. More than 100 pregnant women gave birth between December 2013 and January 2014 and survived, thanks to their efforts.

In Lanyi, located in Western Equatoria State’s Mundri East County, unlike some other areas of South Sudan where fighting was severe, the conflict was limited to opposition forces raiding the town for supplies. Armed men moved through the roadside town, taking food, water, cell phones and other supplies, but left after a couple of days.

The community returned to their homes after spending two nights in the bush, with two new healthy additions—Alice and Jaminewa. And, the story of how a woman volunteer sought to safeguard the lives of her neighbors by ensuring access to misoprostol is already being told again and again in this rural area.

Catharine McKaig is with Jhpiego.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.