FrontLines: What makes Sudan unique from the other places you’ve lived and worked?

Bill HAMMINK: Sudan, which is, of course, now two countries, was a truly unique experience because you had a situation where after almost three decades of civil war, there was an internationally accepted Comprehensive Peace Agreement [CPA] signed and approved by both sides, the north and the south in 2005. The CPA, witnessed by major international powers and international organizations, laid the framework for all of the processes leading up to the elections and the southern referendum, and the outcome of the referendum, which was an independent South Sudan.

And so it was a situation where we were working both diplomacy and development to implement the CPA. And at the same time, we were working closely with the government in the north on implementing the Darfur peace agreement and trying to find ways to support a peaceful settlement in Darfur and expand our assistance from solely humanitarian to recovery programs.

What made Sudan especially unique was the fact that, under the CPA, there were two governments and two systems within one country. There was one USAID mission, although we had two big offices working with two separate governments.

FL: Looking back on your more than two years as mission director in Sudan, what do you see as USAID’s main accomplishments there?

HAMMINK: I would say the major accomplishment for USAID was a peaceful, on-time, and internationally accepted referendum for the people of South Sudan.

And the main instrument in the peace accord, the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, was in fact the right of the people of Southern Sudan to decide what their future would be. It was a process of self-determination. That was a true highlight.

At the same time, USAID managed a major development program in the South since the CPA was signed in 2005, and we had some really exciting accomplishments as an agency. One was in building the capacity of the Government of Southern Sudan, which basically started from scratch in 2005.

In 2011, when the CPA came to an end and the referendum was held, it was a government with ministries with a legal framework and procedures—very nascent, but which had started from scratch.

USAID contributed a lot in capacity building, institutional development, building procedures, all working toward international standards. For example, USAID supported the Ministry of Finance to establish a Financial Management Information System, which allowed accountability and transparency across the board for their budget.

FL: So would you say it was more of a long-term process, laying the foundation where Southern Sudan could become its own country?

HAMMINK: I’d say it was both—a long-term process (and five years is really not nearly long enough; it’s going to be a generational capacity-building endeavor), as well as very short-term types of interventions. For example, when conflict broke out in the south between southerners, USAID used a transition, conflict-mitigation approach—small, short-term grants, that are very focused and targeted—to support reconciliation and peaceful coexistence.

FL: What was it like for you personally to be in Juba on July 9th? Can you describe that day?

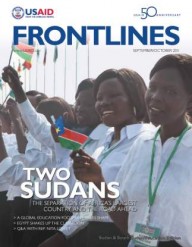

HAMMINK: It was obviously very exciting. July 9th was both at the same time the end of the CPA interim period and it was also Independence Day for the new Republic of South Sudan. And it was incredible. There was electricity in the air. There were multitudes of people celebrating. And the excitement didn’t just happen on July 9th. It started many days before that. I hardly slept.

And then came the official events of the day, when some 30 different heads of state came from across Africa. Juba was full of motorcades. The president of South Sudan spoke about independence, spoke about human and economic rights after decades of civil war. And then President [Omar Hassan al-] Bashir from Khartoum spoke about the fact that the two countries, Sudan and South Sudan, needed to continue close relationships, needed to continue their trade, commerce and cultural linkages, because they have been together since independence in 1956. Overall it was an exciting time, but I think afterwards people realized that it was just the start of what will be a long process of building a new nation and a new state.

FL: What do you think it means for the United States and for Africa that this referendum went through so peacefully?

HAMMINK: In the ’70s and in the ’80s in Sudan, there were peace agreements that were signed between the south and the north, but each time they broke down. So for the United States and for Africa, this was both an end of a decades-long process, not only of civil war but of a peace process. It was also the end of six years of working together under the CPA and reaching a point where you not only had the peaceful and on-time referendum, but agreement by all sides and the international community on the outcome and legitimacy of the referendum.

FL: What goes on behind the scenes as far as U.S. diplomatic and development collaboration in the referendum process?

HAMMINK: I think one of the big successes of the referendum was the role of U.S. Government diplomacy and development working hand in hand. On the diplomacy side, you had the presidential special envoy, who at that time was Gen. Scott Gration; you had the special ambassador, Princeton Lyman, working with USAID on a near daily basis with the Southern Sudan Referendum Commission, which was based in Khartoum and had an office in Juba with leadership there.

At the same time, you had the development side, where USAID took a leadership role in providing a broad range of assistance for the running of the referendum and for the conduct of the referendum—including ballot and polling materials—and for the registration of voters. So you had the political push from the diplomatic side and then you had continual support for the process itself.

USAID also provided electoral observation, both domestic and international, through well-known international groups that we supported, including the Carter Center and the National Democratic Institute, as well as significant support for indigenous or Sudanese civil society involvement in monitoring the referendum.

The other thing to remember is that national elections were held in April 2010. And the process of running those national elections with USAID support significantly contributed to the government and the referendum commission being able to carry out the referendum in a very short time period on time and in a peaceful manner.

FL: How has USAID responded to conflict that erupted in Abyei in May, and in Southern Kordofan in June, displacing tens of thousands of people?

HAMMINK: First a little background: As part of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, it was agreed that there would be a similar referendum for self-determination that would happen concurrently in Abyei—a small area right between the north and the south that has been under dispute for decades, even under the British.

Unfortunately, the north and south could not agree on who could vote. So after the referendum in the south, the situation in Abyei had gotten worse due to uncertainty. There were a few unfortunate incidents between the militaries of the two sides. The Sudan armed forces sent their forces into Abyei, and the people of Abyei fled to the south, leaving a very large number of internally displaced people, or IDPs, in Southern Sudan.

There wasn’t a lot of fighting, but the population was hugely affected. USAID quickly mobilized and provided support to the U.N. agencies and to local and international NGOs working in support of those IDPs.

Luckily, those actors had prepositioned a lot of emergency assistance in that general area, including food aid, tents, tarps, and other types of emergency assistance. So within a week, they had gotten out there, and a lot of that assistance came from USAID.

FL: Some people have expressed concern that with South Sudan’s independence, attention has been lost on Darfur, where conflict continues more than eight years after it began. Does South Sudan’s independence change the situation for Darfur, and is USAID’s approach to Darfur changing?

HAMMINK: Darfur presents to the United States a very complex and difficult situation and USAID’s position vis-a-vis Darfur is definitely changing. Since last year, I think there’s more emphasis on supporting recovery-type programming in Darfur and not solely humanitarian assistance or life-saving support for people in camps, even though ensuring that internally displaced people in camps have the necessary humanitarian, life-saving support is still a focus.

FL: Could you just give a few brief examples of what type of recovery programs we are talking about?

HAMMINK: Yes, we’re talking about agriculture; talking about seeds; talking about support for new technology; fixing schools and water points. Where it makes sense and is the right thing to do, we’re talking about supporting local reconciliation and local groups that want to work together. We’re talking about fixing local clinics so that people can have access to health care. So it’s a broad range of recovery development programs, but it’s still very basic because there’s just very little there now.

FL: Along those lines, can you describe the base line at which we are developing in South Sudan?

HAMMINK: There’s a major need for infrastructure across the board in South Sudan. Most countries, when they come out of conflict or post-conflict, you talk about reconstruction, whereas in South Sudan, you’re really talking about construction. There was so little investment there over the decades since independence, that they have almost nothing.

USAID is building the first major tarmac road in all of South Sudan. South Sudan is about the size of France, and if you can imagine no tarmac roads outside of a few of the cities… The road we’re building is 192 kilometers between Juba, the new capital of South Sudan, and the Ugandan border.

The Agency also constructed about 262 kilometers of all-weather road in Western Equatoria state which has made a huge impact on the security there, as well as allowing agriculture products to be marketed. We put in three electrical systems in three different market towns and we contributed significantly to the water system in Juba itself.

Juba, which is now a nation’s capital, was basically still a garrison town in 2005, meaning the armed forces from the north still controlled Juba. And it didn’t change hands to the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) until after the peace agreement was signed in 2005. At that time, nearly all the infrastructure—the sewer system, the electrical system, the water system, and the road system—dated back to pre-independence days before 1956. During the time of the wars and between the wars, there was very little investment there.

So again, not only is South Sudan starting from scratch in terms of the institutions and new government and a new legal framework, but also in terms of infrastructure.

FL: What are some of the most affecting memories or experiences you take away from your time in Sudan?

HAMMINK: I’d definitely say it was Independence Day when I was up on the stands with other diplomats and VIPs and looking out and seeing over a hundred thousand South Sudanese. When the flag was raised on South Sudan for the first time, you could just feel the earth trembling. People were clapping and shaking and jumping around. And, you know, there was just this palpable excitement in the air.

Another important memory was when Administrator [Rajiv] Shah came and visited some agriculture fields. He was talking to the farmers, local officials, and the minister of agriculture, making it clear the high level of interest USAID had in supporting agriculture to improve food security but also to diversify the economy and make a transformational change in agriculture. He made it clear to the government and people of Southern Sudan that USAID intended to be a major and transformational partner to expand agriculture in Southern Sudan, which has so much potential.

FL: Are you optimistic for the future of Sudan and South Sudan?

HAMMINK: I’m cautiously optimistic. Clearly, change is going to take time, especially when only 15 or 20 percent of the population are literate, especially when they have some of the worst health—maternal and child mortality—statistics in the world.

But the Sudanese people are incredibly gracious. They’re incredibly interested in improving their livelihoods, improving their situation, and I think the excitement from the whole referendum, the independence, will now lead over in the south to doing the right thing in terms of the policies for health care and for education, for accountability and transparency, for anti-corruption. But clearly the jury’s out.

It’s a brand-new country, and they’ve only had five years of trying to put in systems and institutions and procedures, and train people to make it work. And so it’s going to take a lot of continued partnership and support from the international community and from USAID.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.