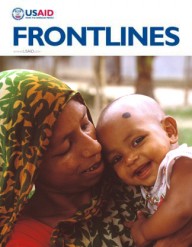

In its first year, Saving Mothers, Giving Life contributed to a rapid decline in the number of women who die in pregnancy and childbirth in eight pilot districts across Uganda and Zambia.

Merck for Mothers

In its first year, Saving Mothers, Giving Life contributed to a rapid decline in the number of women who die in pregnancy and childbirth in eight pilot districts across Uganda and Zambia.

Merck for Mothers

In its first year, Saving Mothers, Giving Life contributed to a rapid decline in the number of women who die in pregnancy and childbirth in eight pilot districts across Uganda and Zambia.

Merck for Mothers

In its first year, Saving Mothers, Giving Life contributed to a rapid decline in the number of women who die in pregnancy and childbirth in eight pilot districts across Uganda and Zambia.

Merck for Mothers

The Matanda Rural Health Center (RHC) in Lundazi district, near Zambia’s northern border with the neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo, is typical of many small health outposts in sub-Saharan Africa: under-staffed, poorly stocked and remote.

In June 2013, a woman in labor named Helen* arrived at Matanda RHC.

Everything seemed normal. It’s the type of scene that takes place dozens of times a day at rural health centers across Zambia. But Helen suffered from postpartum hemorrhage and began to bleed excessively not long after successfully delivering her baby.

For too many women, the story ends here: A tragic, preventable death that will, in turn, significantly reduce the chances that her newborn child will survive and flourish. Nearly one woman every two minutes dies from complications of pregnancy and childbirth—a situation that remains a particularly urgent challenge in sub-Saharan Africa, where more than half of all global maternal deaths occur.

That didn’t happen here, however. Esther Kabaye, who at the time was the sole clinician at Matanda RHC, quickly used her hands to compress the uterus, effectively stopping the bleeding and saving Helen’s life.

Kabaye, who is a skilled birth attendant, credits training she received through Saving Mothers, Giving Life for saving the mother’s life. “With the support that [they] have given me,” she says, “I am so happy to be able to effectively handle emergencies and save lives which would have been lost.”

Saving Mothers, Giving Life, or SMGL, is a public-private partnership started in 2012 to dramatically reduce maternal and perinatal mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. It addresses the three top issues that keep women from receive lifesaving care: delays in seeking care, accessing care and receiving quality, respectful care. And it supports and trains health care workers by reinforcing health systems in countries with few resources, but lots of patients in need of services.

It is also working to improve supply chains to ensure facilities have the equipment, commodities and medicines patients need. SMGL builds on the platform of the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV and to treat women who are HIV-positive and pregnant, who have an eight-times higher risk of death than their counterparts who do not carry the virus.

In its first year, SMGL has contributed to a rapid decline in the number of women who die in pregnancy and childbirth in eight pilot districts across Uganda and Zambia. SMGL achieved a 30 percent decrease in the maternal mortality ratio in the target districts of Uganda and a 35 percent reduction in target facilities in Zambia.

In Zambia, SMGL helped generate a 35 percent increase in deliveries taking place in a health facility, and the number of facilities that could provide basic emergency obstetric and newborn care services increased from three to six. The initiative also drove an 18 percent increase in HIV-positive women who sought treatment for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV, and significantly reduced the number of facilities experiencing stock outs of livesaving medicines like oxytocin and magnesium sulfate.

“The results … are evidence that smart, focused investments can help reduce maternal mortality. Saving Mothers, Giving Life is creating an environment in which safe labor and delivery, in well-stocked facilities with trained professionals, is the new standard of care in Uganda and Zambia. We’ve built a catalyzing model that, when taken to scale, can help ensure that unforeseen complications don’t end in tragedy,” said Robert Clay, USAID deputy assistant administrator in the Bureau for Global Health.

Back at Zambia’s Matanda RHC, Kabaye realizes she may not have been able to save Helen’s life if the woman had arrived at the health center one year earlier. Back then, Kabaye lacked the training, equipment, medical supplies and confidence to perform the duties necessary to help Helen—not to mention the fact that the nearest referral hospital is 60 kilometers away. But now Kabaye is armed with the tools and skills to deliver prompt, lifesaving care in even the most dire of emergencies.

Many health workers in developing countries face similar challenges, lacking the necessary equipment, skills and experience to effectively manage complications like preeclampsia/eclampsia and postpartum hemorrhage.

Elsewhere in Zambia, SMGL offers training to Safe Motherhood Action Groups (SMAGs), teams of community health workers who help guide pregnant women in their village through a safe and healthy pregnancy and childbirth experience. One SMAG, a man named Edson Zulu, proudly reported on his newfound ability to educate women on safe motherhood and connect them to nearby facilities for maternity care.

Thanks to SMAG, said Zulu, “we have seen an increase in the number of women coming to deliver, and women are coming early and more frequently for care before delivering.” Talking about the results of his work, he added, “we are working to save lives in our communities.”

*Last name not available.

This article was written jointly by the staffs of the Peace Corps, USAID/Zambia and Saving Mothers, Giving Life.

USAID, the Government of Norway, Merck for Mothers, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Every Mother Counts, Project C.U.R.E., the U.S. Departments of State, Defense, and Health and Human Services, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Peace Corps

Related Links

Women Now “Crossing the River” Safely in Cambodia

By Christophe Grundmann

For generations past, crossing a river in Cambodia entailed navigating a leaky canoe across churning, turbulent waters, with little chance of being saved if things went wrong. Equally as dangerous for past generations was the act of childbirth.

Traditionally, women would deliver their babies at home accompanied by either a relative or a traditional birth attendant with only rudimentary skills. If something went wrong during birth, chances were that the baby—or mother—would die; hence, the old Khmer metaphor referring to childbirth as “crossing the river,” or chlong tonle.

In recent years, however, the Government of Cambodia, supported by USAID and other partners, has made substantial progress in reducing the risks of pregnancy and childbirth—and lowering the rate of maternal mortality.

Two decades ago, a typical Cambodian village of 1,000 people would lose a woman to pregnancy-related complications every four years. Today, with rapid advances in pregnancy care and clinical services, a maternal death is likely to occur in that village only once every 32 years.

This means most women older than 30 remember a friend or neighbor dying while “crossing the river,” while younger women now see the risks of childbirth as being very remote.

In Toul Chra Neang village of Battambang province, 34-year-old Hout Pharout remembers two cases of village women dying of postpartum hemorrhage after delivery when she was in her early teens.

“The women both died from bleeding after delivery, as they were not able to get to the health center. One of the surviving infants was adopted by another family, and the other is living in the village with her father,” Pharout said. “That was about 20 years ago. I was afraid when I heard the stories. When I gave birth, I felt worried as old people always said it was dangerous to cross the river, which is why I delivered my three children at the health center.”

USAID has been the largest donor in the maternal and child health sector in Cambodia for two decades, supporting a number of activities to improve maternal and newborn health. Many USAID-supported interventions are then taken up by the Cambodian Government, institutionalized and scaled up. Successful examples of this collaboration include a team-based approach to training, which brings public sector doctors and midwives together—regardless of rank and level of education—and uses mannequins and real-life cases to improve skills.

These investments by USAID and the Cambodian Government have made an impact. In the past 13 years, antenatal care has doubled to 89 percent, with those making at least four visits to a health provider during pregnancy rising from 10 percent to 69 percent. The percentage of births attended by a skilled birth attendant rose from 32 percent to 71 percent, and the percentage of deliveries taking place in public health facilities jumped from 10 percent to 64 percent.

The success of these programs means that younger women, like Dam Chan, who is 23 years old and has two children, have, she says, “never heard of any women dying during delivery. I just delivered my second child two months ago. When I was pregnant, I always went to the health center for check-ups every month and I delivered at the health center and stayed there overnight and come back home safely. My 2-month-old son is healthy because I breastfeed him.”

Christophe Grundmann is with University Research Co. LLC.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.