Tennesha Rhule conveys her story to members of the U.S. Embassy community at an HIV forum in 2012.

USAID

Tennesha Rhule conveys her story to members of the U.S. Embassy community at an HIV forum in 2012.

USAID

Tennesha Rhule conveys her story to members of the U.S. Embassy community at an HIV forum in 2012.

USAID

Tennesha Rhule conveys her story to members of the U.S. Embassy community at an HIV forum in 2012.

USAID

For the past three years, 27-year-old Tennesha Rhule has spent her life venturing into areas where many Jamaicans would never even set foot. As a community peer educator for the Jamaica Ministry of Health, Rhule’s job entails educating youth and adults in some of the country’s most volatile communities about HIV and how to practice a safer and healthier lifestyle.

On a typical day, Rhule travels to a local health clinic and several inner city communities, and will round out her evening with visits to exotic night clubs and massage parlors.

“A lot of persons are fearful to go to the clinic to get tested. That is one of the main reasons people don’t get tested and then don’t know their HIV status,” she said. “So the job has taken me to areas that even I myself would not have even dreamed of going to, but it is important because I am able to build personal relationships with my clients and am able to convince them to get tested as well as to practice safer sex.”

Today, Rhule is one of 10 counselors in the Kingston and St. Andrew division supported by USAID working the streets of Jamaica to stop HIV from spreading. Rhule admits she had an unconventional path to the work she sees as a calling.

Following the Crowd

In 2007, as a 19-year-old single mother struggling to raise two children, Rhule rented a room in one of Kingston’s most volatile areas, Back Bush. There she worked as a bar hostess serving drinks to customers.

“It was hard, making very little money and trying to pay the rent and bills every month,” she said.

The pressures of society soon got the best of her. “I remember seeing my housemates get dressed every night for work,” she said. “[They] would always have a lot of money to buy new clothes and the most expensive of things, and I remember saying to one of them ‘Take me to your work, because I want what you have.’ The girls then told me to put on the sexiest outfit I had.” She knew what she would have to do next.

In the commercial hub of the capital city, New Kingston, Rhule began soliciting as many as five clients per night and earning up to $120, 12 times more than her previous salary as a waitress.

“At first I was nervous, but after, when I saw the amount of money I earned in one week, I was excited. The job was like drugs and if you are not careful, you would get carried away,” she said.

For three years, Rhule hustled the streets of New Kingston as a commercial sex worker. At the same time, she began taking classes in mathematics, English and accounting. She also signed up for a workshop on HIV put on by the Jamaica Ministry of Health (MOH) in 2008. It was there that she met MOH counselors and knew she should be doing more with her life. HIV outreach was her calling.

By the next year, the harsh realities of the streets forced her hand.

“I remember a client holding a knife to my neck when I was in the car, and he cut my throat and physically assaulted me,” she said. “It was at that point I knew I had to get out of this job.” A little over one year later, she began at the ministry as a peer educator.

Use a Condom, Every Time

In 2009, under the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, the United States established its first efforts to combat HIV in the Caribbean and created a regional HIV prevention and care program, including the peer educator program in Jamaica.

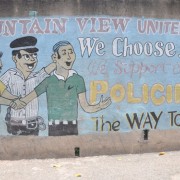

USAID provides assistance through the MOH and community-based organizations that are implementing HIV prevention programs targeting key populations. USAID also works to address stigma, gender norms, and gender-based and sexual violence.

USAID/Jamaica HIV Specialist Jennifer Knight-Johnson said: “Our data shows that almost 50 percent of persons living with HIV/AIDS do not know their status and this creates an enormous public health challenge for treatment and care. It is important for us to continue to go out and interact with persons in the community and increase our advocacy on the importance of safe sex—using a condom every time is our mantra.”

There are an estimated 32,000 Jamaicans living with HIV. While that equates to a prevalence rate in the general population of 1.7 percent, the rate is 4.1 percent for sex workers and jumps to 32 percent for men who have sex with men.

“The work that Tannesha and other Ministry of Health workers are doing— they are the backbone of the HIV program,” said Knight-Johnson. “They are the ones who go into the communities and have one-to-one counseling, conduct HIV tests and condom demonstrations, conduct empowerment workshops, go into the schools and talk about the basic facts of HIV.”

Goodbye Evil City

Rhule’s passion and drive to educate her peers about HIV goes beyond her job. In 2002, her older sister contracted the virus.

“The issue back then was that there was no information readily available about HIV/AIDS, and the stigma associated with it was even higher than it is today,” said Rhule. “I recall asking the doctors a lot of questions about the virus and reading up whenever I could. It was important to me. I remember back in 2005 my sister was bedridden at the local hospital with scars on her skin as a result of the virus and I was determined at that point to nurse her back to good health.”

Today, her sister is alive and healthy, and volunteers her time at a local community center, knitting and sewing. She continues to take her antiretroviral medication.

Spared from the virus herself, Rhule says she is fortunate to be HIV-negative and has been given a second chance at life so she could help others to practice safer and healthier lifestyle choices.

“My first day at the ministry was January 11, 2011,” said Rhule. “I remember going back on the streets of New Kingston the night before. Looking around, I said to myself, the streets were my university, but now goodbye evil city.”

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.