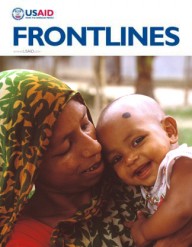

Chikondi Damiano, now 2 years old, was protected from mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

Tawanda Shumba, Jhpiego

Chikondi Damiano, now 2 years old, was protected from mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

Tawanda Shumba, Jhpiego

Chikondi Damiano, now 2 years old, was protected from mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

Tawanda Shumba, Jhpiego

Chikondi Damiano, now 2 years old, was protected from mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

Tawanda Shumba, Jhpiego

You have probably never been to the Kwamwankulu Village in Malawi, 20 kilometers south of the capital Lilongwe. Despite Kwamwankulu’s anonymity, with its long, red-dirt roads and baobab trees, many, including Milica Damiano, call the village home.

Two years ago, Damiano was five months pregnant and making her first prenatal visit to the Nathenje Health Center, a facility supported by USAID through the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR. The baby had a strong heartbeat and was growing well. Damiano, on the other hand, was feeling sick, a condition she attributed to the pregnancy itself.

As part of the health checkup, Damiano received an HIV rapid test and discovered that she was HIV-positive. She quickly began taking antiretrovirals (ARVs)—medicine that prevents the virus from replicating and helps restore the immune system—and was advised to bring her husband, Chasowa, in for testing. He tested positive as well and, over the following four months, they both took ARVs daily. As their strength grew, so did Damiano’s waistline.

Damiano is one of the approximately 600,000 women in Malawi who get pregnant every year and seek prenatal care. Many of these women receive care through USAID’s Support for Service Delivery Integration (SSDI)-Services project. Started in 2011, SSDI’s goal is to prevent new pediatric HIV infections as well as improve family planning, malaria prevention, nutrition and neonatal resuscitation services for new mothers. The project is a partnership between Jhpiego, Save the Children, CARE and Plan International.

Each day, nearly 1,000 children become newly infected with HIV globally. Under-resourced countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, are especially hard hit, while the number of new HIV infections and related deaths among children in well-resourced settings are near zero. Worldwide, many pregnant women remain unaware of their HIV status, and many that are known to be positive do not receive drugs to prevent transmission of the virus and protect the health of the mother.

When HIV-infected mothers do not receive ARVs, up to four of every 10 babies are infected. When antiretroviral drugs are used to protect the mother and baby, however, HIV transmission can be reduced to less than 5 percent, and maternal mortality can be reduced as these drugs also restore the mother’s immune system. As babies are known to die more often when their mothers are sick or deceased, protecting the health of mothers remains critical for all children in the family, regardless of HIV status.

Over the past decade, with USAID support, over two dozen countries have made significant progress in rolling out programs to stop new pediatric HIV infections. As a result, the prevalence of HIV infection and the number of new pediatric infections has declined.

In 2011, Malawi’s Ministry of Health adapted World Health Organization guidelines in an effort to further minimize new pediatric HIV infections and keep Malawian mothers alive and healthy. With USAID and PEPFAR support, Malawi has significantly scaled up its HIV treatment program and is on its way to achieve an AIDS-free generation. Between October 2012 and September 2013, over 100,000 people were started on lifesaving HIV treatment.

This new strategy, known as “Option B+," offers life-long HIV treatment to all pregnant and breastfeeding women living with HIV. Malawi’s national HIV treatment program, which offers HIV services and drugs free of charge, pursued Option B+ for one primary reason—its simplicity. Option B+ offers an easy-to-understand, one-size-fits-all approach that enables women to initiate and remain on lifesaving treatment.

Since the beginning of nationwide implementation in July 2011, Option B+ in Malawi has led to a large increase in those receiving treatment, with a nearly eight-fold increase in the number of pregnant women being enrolled in HIV treatment as of September 2012. With these documented successes, Option B+ is now a critical element of a larger national strategy in which Malawi’s HIV treatment and antenatal programs are fully integrated and ARVs are administered by nurses at primary care facilities where both HIV-infected and uninfected pregnant women access services.

Today, approximately 60 percent of the 5,000 HIV-positive women in Malawi getting pregnant every month receive ARVs. Facilities like the Nathenje Health Center are able to support HIV testing for over 400,000 Malawians each quarter. Option B+, after showing such promising results in Malawi, has been adopted by WHO and is now being implemented in over 10 countries in and beyond sub-Saharan Africa.

As for Damiano, four months after her first prenatal visit, she returned to the Nathenje Health Center to give birth to her son. Together, they attended regular follow-up visits, with Chasowa when he was able. The baby received both Nevirapine and Bactrim to protect him from becoming infected with HIV and guard against opportunistic infections. Damiano and her husband continue to thrive on ARVs. Their son, named Chikondi, which means “love” in Chichewa, is now 2 years old … and HIV-free.

Damiano recently shared her story at a Jhpiego anniversary celebration in Malawi. “I am very grateful to the service providers at Nathenje Health Center for having enrolled me into the PMTCT [prevention of mother-to-child transmission] program,” she said. “It is through the interventions of the program that my son was born HIV-negative and is still HIV-negative up to now.”

Catherine Gotani-Hara, Malawi’s minister of health, was also at the event. “I would like to applaud Milica Damiano for coming out in the open to talk about her story,” she said. “This story will encourage other women and men who do not have the courage to go and get tested … Milica, you are very, very brave.”

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.