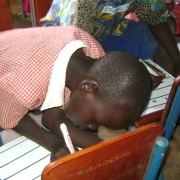

A peer educator mobilizes clients for outreach services in Kawempe.

Geoffrey Ddamba

A peer educator mobilizes clients for outreach services in Kawempe.

Geoffrey Ddamba

A peer educator mobilizes clients for outreach services in Kawempe.

Geoffrey Ddamba

A peer educator mobilizes clients for outreach services in Kawempe.

Geoffrey Ddamba

Rita Murungi is a 26-year-old woman from Mbarara, a busy city of 200,000 in western Uganda. She works as a waitress at a restaurant in town and is a regular visitor to a local youth center that hosts daily social events—like team sports and theatrical shows—to provide a safe place for young people ages 15-30 to gather.

The Mbarara Youth Center has another function as well. It is part of International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) affiliate Reproductive Health Uganda (RHU), an NGO committed to providing sexual and reproductive health information and services for vulnerable and at-risk young people.

The problem was that young people like Murungi weren’t accessing these all-too-important services that were quite literally under their noses. Organizers had envisioned a place to empower young people to make informed sexual and reproductive health decisions and break down barriers to contraceptive access, which is used by just 38 percent of sexually active unmarried women in Uganda.

Chrispaul Abaho, a volunteer at the Mbarara Youth Center, explained: “Youth would come to the center to access recreational activities, but would not come for health services. For instance, Rita knew that services were offered at Mbarara clinic, but she had fear on how to approach the staff [even though] she used to interact with [them] almost daily.”

So, in 2014, staff at the Mbarara clinic participated in the Leadership Development Program Plus (LDP+), a hands-on program that allows professionals at all levels of the health system to learn and practice leadership, management and governance skills. During the six-month program, teams develop a shared vision, analyze what stands in the way of progress, think collaboratively and creatively, and develop innovative solutions to overcome their specific health service delivery challenges. This included everyone from the director of finance to the secondary school-aged volunteers at this and five other clinics that USAID supports in the country. Organizers were confident this behind-the-scenes activity would translate to helping more young people.

During their LDP+ training, the team at the Mbarara clinic focused on increasing youth access to family planning services at their clinic. They identified the lack of collaboration between the youth center, the community and the clinic as a detrimental factor in reaching young people. “Everyone was working separately,” Abaho explained.

But their efforts were deemed critical to improving reproductive health services in a country where currently four in 10 births are unplanned. In Uganda, one in every four teenage girls between 15 and 19 is already a mother or pregnant. Children born to adolescent mothers are less likely to make it to their fifth birthday, and face a substantially higher risk of dying than those born to women ages 20-24.

In addition, girls between 10 and 14 are five times more likely to die in pregnancy and childbirth than women 20-24, and young women ages 15-19 are twice as likely to die. Increasing access to sexual and reproductive health services for youth, including access to modern contraception, is important to achieve Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 4 (reduce child mortality), MDG 5a (improve maternal health) and MDG 5b (universal access to reproductive health).

Adolescent pregnancy is high in Uganda for a multitude of reasons, including lack of information and education, lack of access to youth friendly services, and barriers to access such as stigma and negative staff attitudes. Due to social stigma, many young people in Uganda shy away from reproductive health services. They often don’t want their parents or community members to know that they have a need for family planning services.

The team implemented a new strategy to involve youth in their decision-making and program planning. They began including young people from the community in their weekly meetings and hosting monthly health education talks at the youth center. “We began to plan jointly for both the youth center and the clinic at the same time. We would now collaborate with each other,” Abaho said.

Murungi attended one of these new monthly health education talks and had a chance to speak with a nurse privately afterwards. She described the experience as transformational, saying, “It’s not that I didn’t know where to go for services, but I was scared of whom to talk to and how to explain everything. But now, I am using a three-month injection for family planning to avoid unwanted pregnancies.”

Donanta Muhureze, a staff member at the youth center, says “the [LDP+] has not only improved youth participation in addressing their own needs, but also contributed to the client load for the clinic because many now freely visit the clinic for services.”

Today, the Mbarara clinic serves well over 500 family planning clients monthly, an increase of over 350 percent from 2013.

But could the same techniques work for sex workers, a far more difficult population to reach? Kawempe, in the outskirts of Kampala, Uganda, faced a much higher rate of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and a lower rate of contraception use than other towns in 2014. The Bwaise clinic there was serving only 1,400 clients a month—a number staffers knew was far too low to include many of the people who needed services the most.

“By participating in the LDP+, we found that we needed new outreach [strategies] and messaging for both clients and service providers,” said Mariam Hamed, the in-charge service provider at Bwaise.

Staffers found how commercial sex workers could be reached, where they typically worked and who the gatekeepers were for this community. They reached out to unlikely partners, including sports-betting companies and boda-bodas (motorcycle taxis) to conduct educational and peer-to-peer learning sessions on family planning and STI prevention and treatment.

Equipping and empowering sex workers themselves (dubbing them “moonlight stars” to lower stigma) as well as potential clients to conduct peer-education in non-clinical, social settings allowed the clinic to reach new underserved populations. Peer educators would go anywhere young people gathered to provide condoms, sexual and reproductive health information, and referrals to Bwaise for services.

“When we started this line of work, [sex workers] were surprised because they are normally stigmatized. But when a peer educator talks to them, they welcome it,” said Hamed.

By encouraging male involvement, conducting worksite educational sessions, and developing partnerships with the private sector and community leaders, the Bwaise clinic more than doubled its client numbers after just five months.

“We encouraged the men to bring their partners. This would help us map the social networks and identify sex workers. The network would really grow,” explained Hamed. “We used new messages for peer educators to encourage sex workers to use condoms and seek treatment without feeling stigmatized.”

The clinic now sees well over 3,500 clients a month, an increase of over 250 percent. Clinic staffer Fred Ssemakula said that “LDP+ is realistic and brings life to our programs … it breaks boundaries to quality care.”

Sasha Grenier is a senior technical officer with the Leadership, Management and Governance Project.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.