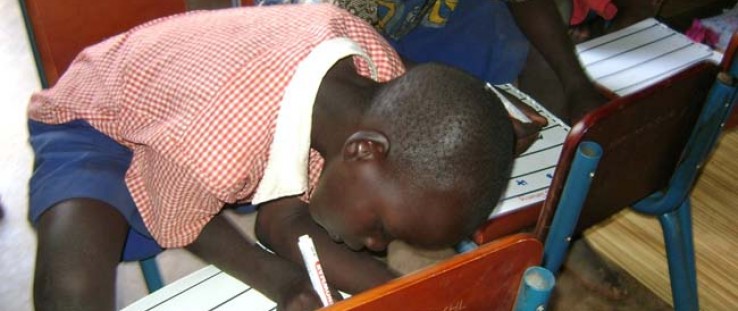

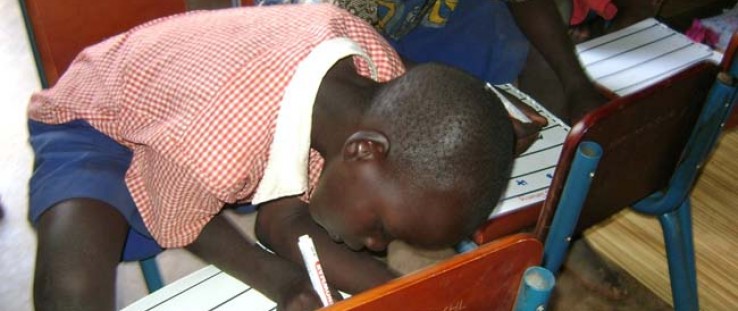

USAID's UNITY project, working with the Uganda Ministry of Education and Sports, is helping dyslexic children like Brian.

USAID

USAID's UNITY project, working with the Uganda Ministry of Education and Sports, is helping dyslexic children like Brian.

USAID

USAID's UNITY project, working with the Uganda Ministry of Education and Sports, is helping dyslexic children like Brian.

USAID

USAID's UNITY project, working with the Uganda Ministry of Education and Sports, is helping dyslexic children like Brian.

USAID

Jessica Ilomu, a USAID education specialist, watches carefully as a child at St. Goretti Demonstration School in rural Lira district, Uganda, copies down an exercise from the board given by his teacher.

The child begins with his name—A-y-o-r-i B-r-a-i-n. Immediately, Ilomu notices something is wrong: the child’s name is Brian. She also realizes why he has repeated this grade level multiple times. A pleasant and attentive child, Brian has dyslexia, which causes difficulty in processing symbols and determining the meaning of simple sentences. Unfortunately, it is has taken three years for Brian’s problem to be recognized.

Brian is not the first, and certainly not the last, student in Uganda who will be diagnosed with a learning disability. In his case, teachers juggling classes of around 120 students never had enough time to follow up on each learner. The average recommended student-to-teacher ratio for dyslexic students is 10 to 1.

Uganda, with aid from USAID, is taking deliberate steps to make its education programs more inclusive for young people with disabilities. As many as 184,000 children in Uganda are considered to have some kind of disability that makes it difficult for them to learn.

Institutionalizing Special Needs Ed

The Government of Uganda did not adopt legislation related to people with mental, physical, or learning disabilities until 1983, when the Ministry of Education and Sports (MoES) established a unit for special needs education. However, it was not until 1995 that the country’s constitution was updated to make education a basic right for all Ugandan children. Historically, special needs education has come from wealthy individuals, NGOs, or more broadly, well-wishers—not the government. The result: a fragmented, ad-hoc approach lacking structure.

That is now changing. Within the last decade, MoES has made access, quality, and equity a key strategic objective, and has created the Department of Special Needs and Inclusive Education to ensure that education programs are customized to address special needs learners.

Since 2007, the USAID-funded initiative known as the UNITY project has been supporting the department to implement a series of initiatives aimed at establishing, mainstreaming, and institutionalizing special-needs programs throughout the Uganda education system. In 2008, with UNITY support, curriculum was adapted to target gaps in special needs education. Printed copies were distributed to classrooms and over 900 teachers received training.

After the first cohort of teachers was trained in the five specialist areas in April 2010, teachers asked for additional training to address visual and hearing impaired children, mental retardation, and children like Brian with dyslexia.

Natasha DeMarcken, senior education adviser for USAID/Uganda, notes that, “The Ministry of Education and Sports has now taken a bold and strategic step to pilot a functional assessment program in primary education. The teachers who have been involved in the program feel much more empowered and skilled to handle learners in an inclusive learning environment. The additional skills equip teachers beyond what they are exposed to in the mainstream teacher training programs.” Over 3,100 teachers have now been trained in specialized skills.

In recent months, schools like Brian’s have begun taking the critical first steps in educating special needs learners. In addition to training teachers, officials hope to raise awareness and mobilize parents of students with disabilities, community-based organizations, health service providers, and most critically, government leaders.

“We want to leave behind a critical mass of people in order that this can be continued, and in order that a scale-up can take place,” said Patrick Bananuka, an officer with UNITY. “People tend to look at disabilities; we are looking at barriers. These are entirely different points of departure.”

This consensus-building approach is a fundamental step to ensure the sustainability of these efforts, and has effectively put special needs education on the national agenda. MoES is expected have a well-developed special needs education policy by the time the UNITY project closes in November 2011.

One component of this policy—its focus on research and technology—is one of several USAID education strategic principles. The policy is also characterized by its innovation, country ownership, and advanced evaluation practices, said Martin Omagor, commissioner of special needs education/inclusive education within the Ministry of Education and Sports.

“This means Uganda is far ahead of other East African countries in institutionalizing special needs education: most other countries have special schools rather than mainstreaming special needs education,” said Jeremiah Carew, acting USAID/Uganda mission director. “Once this policy is in effect, USAID will have laid a solid foundation on which all children with learning barriers will have a more supportive, secure, and inclusive learning environment. These are significant accomplishments that USAID can point to when discussing USAID’s work for people with disabilities with advocacy groups in Uganda.”

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.