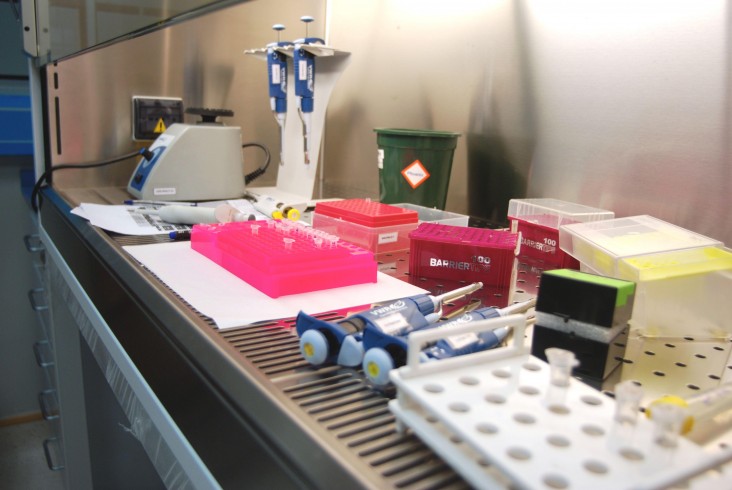

A scientist tests cases at the DNA facility in Sri Lanka.

USAID

A scientist tests cases at the DNA facility in Sri Lanka.

USAID

A scientist tests cases at the DNA facility in Sri Lanka.

USAID

A scientist tests cases at the DNA facility in Sri Lanka.

USAID

Sri Lanka saw an end to its 26-year conflict in 2009. And like other post-conflict settings throughout the world, the island nation in the Indian Ocean experienced a disturbing level of violent crime—from rapes to homicides to unexplained deaths—in the aftermath.

In 2010 alone, Sri Lanka Police Service statistics revealed that more than 91 percent of homicides and 96 percent of rape and incest cases reported to the police were in limbo. The snail-paced conviction rates are due to several reasons, but weaknesses in forensic sciences is considered a major one.

Even today, the conviction rate for those crimes in the country hovers around 4 percent.

Enter DNA analysis, a 30-year-old technology that continues to prove itself a powerful crime-fighting tool.

In 2011, USAID and the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) partnered with the Government of Sri Lanka to establish a state-of-the-art DNA laboratory, complete with top DNA analysis programs as well as other functions necessary for crime investigations. The laboratory is housed at the Government Analyst’s Department (GAD) of Sri Lanka, which was established in 1904 as the central government facility to provide services to law enforcement authorities in the areas of crime investigation and public health.

“The DNA technique is not a new one. It was first introduced three decades ago. This is the technique to identify a suspect and then prove conclusively that the suspect is or is not the perpetrator of a particular crime. The results are conclusive, therefore, no one can challenge them,” said Sakunthala Tennakoon, the Sri Lanka government analyst. “We have been trying to get DNA testing facilities to Sri Lanka for a long time. Our hopes have come to fruition and, today, with the establishment of a fully fledged, government-operated facility that meets international standards, we can serve the entire country and revitalize the criminal justice system.”

Since the laboratory opened in early 2014, officials have referred evidence in 110 cases, including for murder, rape, paternity, burglary and other incidents.

Thanks to DNA testing in Sri Lanka, parents of a child who was abducted several years ago managed to claim the child in the courts after he was found begging on the street; a 15-year-old rape victim was able to prove the perpetrator’s identity when remnants of her clothes and handkerchief were matched with the suspect’s blood sample; a father who killed his two daughters was convicted for the crime when blood stains on the children’s clothes were matched with his blood sample; and a 4-year-old was reunited with his biological father when a buccal swab sample matched the child’s blood sample.

Once a case is produced in courts by the police, body fluids (including blood, saliva and semen), hair, remnants of clothing and weapons from crime scenes are sent to the laboratory. The laboratory performs preliminary tests on the samples to extract what is called a “pure DNA.”

“Generally, it takes around three months to complete DNA testing on one case, but if there is an urgency, the process can be expedited and the results can be released sooner,” says Vaneetha Bandaranayake, an assistant forensics government analyst. Forensic scientists are also called to present DNA evidence in courts at times or to be available for cross examination by the defense counsel.

To rebuild the facility in a way that is useful to the criminal justice system of the country, the partnership also funded training and supplied forensic-related equipment and technology to the GAD. Groups of GAD scientists visited Oklahoma State University for a three-week-long training program in 2012 and 2014. GAD scientists also attended workshops and conferences overseas, took online training programs, and learned advanced techniques from international experts visiting Sri Lanka.

“The training on DNA was in-depth and was based on both theoretical and practical aspects. On our return, we were able to put into use what we learned. Without this training, we could not have handled DNA testing the way we do today,” says Don Jayamanne, head of GAD’s DNA laboratory.

“We are raising awareness among officials from the Judicial Medical Department, magistrate courts and law enforcement units on the availability of the technology,” Jayamanne added. “This is very important, as all this affects the crime and conviction rates long term.”

The establishment of the GAD in 1904 was a large step forward for Sri Lanka as it was the first official establishment that analyzed scientific material for government use. But in this century, the facility was simply out-of-date, forcing both public and private entities to rely on private laboratories for DNA testing at high cost.

“USAID and the DOJ partnership with the Government of Sri Lanka not only helped to get the DNA capability on its feet, but this initiative was a tangible demonstration of U.S. support to help solve crime and minimize its occurrence in the long run,” says Acting USAID/Sri Lanka Mission Director Elisabeth Kvitashvili. “By revolutionizing DNA law enforcement, we hope to strengthen legitimate prosecutions of criminals, strengthen trust in the criminal justice system and reduce the crime rate in the country.”

Today, the GAD has over 70 staffers and the necessary equipment to perform its duties effectively. “We are hoping to develop these facilities further, to make it one of the best, not only in the country, but also in the Asian region, quality- and quantity-wise,” said Tennakoon. “Currently, we have a backlog to clear, therefore, we are only accepting cases for DNA testing from public entities. Once we stabilize ourselves, we hope to expand our services to private entities as well. That way we can make the operation sustainable.”

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.