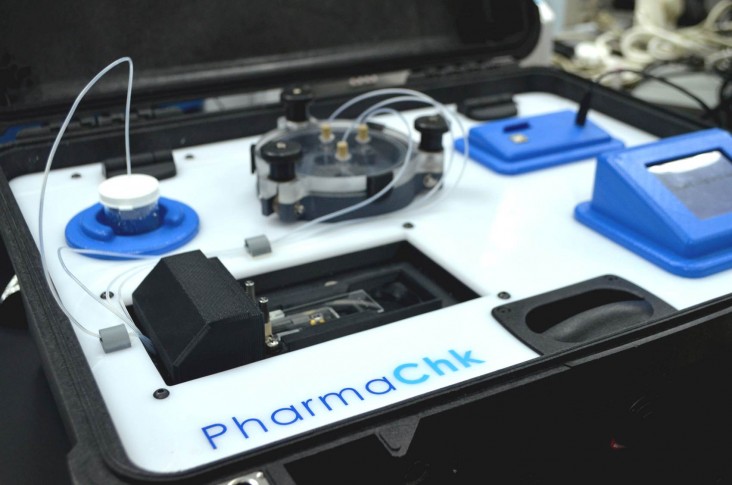

A Ghanian technician in Accra from the U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention’s Center for Pharmaceutical Advancement and Training uses PharmaChk to test malarial drug quality.

Darash Desai/Andrea Fernandes

A Ghanian technician in Accra from the U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention’s Center for Pharmaceutical Advancement and Training uses PharmaChk to test malarial drug quality.

Darash Desai/Andrea Fernandes

A Ghanian technician in Accra from the U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention’s Center for Pharmaceutical Advancement and Training uses PharmaChk to test malarial drug quality.

Darash Desai/Andrea Fernandes

A Ghanian technician in Accra from the U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention’s Center for Pharmaceutical Advancement and Training uses PharmaChk to test malarial drug quality.

Darash Desai/Andrea Fernandes

Imagine rummaging through your medicine cabinet for a vital prescription. Once found, you pop the lid and tap out a few pills into your palm. If you live in a country that strictly regulates pharmaceutical production and distribution, you assume the pills are safe and take them without a second thought.

But what if these protections were not provided? What if you were stricken by an illness that required medication that you couldn’t be sure was safe or effective? What if you learned too late that this medication contained no active ingredient, was degraded, or mixed with toxic components?

For millions of people in developing countries, these questions are all too real.

In 1995, a meningitis epidemic hit Niger, in West Africa. Although the Government of Niger carried out an efficient vaccine program, more than 50,000 people were administered fake vaccines that contained no active ingredient, resulting in 2,500 deaths. The vaccines, donated by a country that thought they were safe, had been bottled and labeled to look like true vaccines.

Similar incidents continue to occur worldwide. Counterfeit drugs, which are estimated to be as high as 30 percent of all drug sales in the developing world, can cause severe side effects or death or, because they often don’t contain the correct amount of active ingredients, can allow for disease progression and cause drug resistance. Globally, more than 100,000 people die every year as a result of these dangerous drugs and this likely represents a significant underestimation. High profit margins and minimal risk, along with lack of political commitment and weak medicines regulation and enforcement drive the counterfeit market.

A parallel problem exists with substandard medicines, whether imported or produced locally. In these cases, drugs are not produced in accordance with accepted good manufacturing practices or shipped or stored properly, rendering them ineffective at best. In 2012, a contaminated cardiovascular medicine was linked in Pakistan to the death of more than 200 patients in just a few days and was responsible for sickening 1,000 after lethal amounts of an antimalarial drug were accidentally mixed with the medicine during manufacturing.

This is the dire and sometimes fatal scenario that a promising and innovative new device called PharmaChk is hoping to prevent. PharmaChk, a fast, easy and inexpensive screening technology for counterfeit and substandard medications, is being developed at Boston University to help combat the perils of poor quality drugs in the developing world.

Several programs at USAID, including Saving Lives at Birth: A Grand Challenge for Development, have backed this effort.

“Our goal is to comprehensively address the limitations of current technologies and provide detailed information on drug quality at all points in the supply chain,” says Muhammad Zaman, an associate professor at Boston University and the lead researcher developing the device.

Zaman, who teaches biomedical engineering, has both a professional and personal interest in combatting counterfeit drugs in the developing world. He grew up in Pakistan and remembers that his “mother would take us all across the town so we could get our medicines and vaccines at a reputable place.” Those long treks would eventually inspire him to tackle the counterfeit and substandard medicine crisis.

In 2011, Boston University teamed up with the Promoting the Quality of Medicines program, a USAID-supported project implemented by the U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention, to help developing countries address critical issues related to poor quality medicines and to confront the problem of detecting counterfeit and substandard drugs in the market. Zaman jumped at the chance to advance this effort. With one of his doctoral students, Darash Desai, Zaman began working on the PharmaChk prototype as a way to “give back to the people who suffer from these challenges.”

To test a medication, a user simply places a drug sample into the briefcase-sized PharmaChk device, which mixes the drug sample with a molecular probe specific to the drug. The reaction between the probe and the drug sample is then quantified by a light receiver embedded within the device to determine the exact amount of the active ingredient present in the sample. The strength of the light indicates the concentration of the drug, which is then measured over time to indicate how quickly the drug dissolves.

This process is fast and automated, with low power requirements and minimal sample preparation and user training required. Results are shown on a digital touch-screen and can be saved on a SD card like those used to store photos in digital cameras. The intention is for PharmaChk to be used at multiple levels of a health system—within health facilities, pharmacies, medicine warehouses, provincial laboratories and at customs border crossings. The developers’ current focus is on high priority essential medicines, including antimalarials and antibiotics.

Many existing devices used in the developing world can determine the presence or absence of an active ingredient; some also test for brand-specific characteristics of the drug and packaging. However, these devices can give only a rough, visual estimation of the amount of active ingredient present at best and cannot indicate whether the drugs will dissolve properly.

Recent studies on antimalarials in Kenya and Pakistan confirm that drugs that have the right amount of the active ingredient, but fail to release in the body are as ineffective as drugs that have no active ingredient. The PharmaChk technology is designed to bridge this gap in existing technologies. PharmaChk also aims to cut down transportation challenges associated with the existing field standard, the MiniLab, which, while portable, is big, heavy and laborious to operate.

A 2014 field test in Ghana showed the PharmaChk device to be 99.6 percent accurate in quantitatively identifying the amount of the drug in an injectable antimalarial medication—one that is now recommended by the World Health Organization as the first-line treatment for severe malaria. In comparison, MiniLab produces a less precise, visual and qualitative determination of drug concentration.

PharmaChk is being refined to have similar accuracy when testing tablets and other drug formulations. In countries where manufacturing practices are inconsistent and poorly regulated and products are subjected to harsh conditions when shipped and stored, it is critical to determine not only whether a product is a fake, but also whether medicines produced legally have been manufactured poorly or inadvertently contaminated or degraded before reaching unsuspecting patients. PharmaChk is intended to test for the latter.

Saving the Most Vulnerable Victims

PharmaChk received a $250,000 seed grant from Saving Lives at Birth: A Grand Challenge for Development because Agency officials saw great potential in the device for its ability to improve health outcomes for mothers and babies, particularly related to malaria infections, which are endemic to 50 percent of the countries in the world and disproportionately affect pregnant mothers in low-income countries.

Saving Lives at Birth—a partnership between USAID, the Government of Norway, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Grand Challenges Canada, and the U.K. Department for International Development—calls on the brightest minds around the globe to develop groundbreaking prevention and treatment approaches for pregnant women and newborns in poor, hard-to-reach communities around the time of delivery.

PharmaChk was also awarded a 2013 USAID Partnerships for Enhanced Engagement in Research grant—a program that directly supports developing country scientists working on research projects with U.S. National Institutes of Health-funded scientists—and was listed as one of Scientific American’s World Changing Ideas 2013.

The developers of PharmaChk plan on doing additional field tests, with an emphasis on priority essential medicines. In the near future, they plan to expand the capabilities of the device to test a larger variety of medicines to advance the goals of ending maternal and child deaths and achieving an AIDS-free generation.

Field trials are not only providing an opportunity to test the functionality of the device, but are allowing the PharmaChk team to meet with key stakeholders in the pharmaceutical supply chain. “Here, we were able to really understand the needs of the people and the government and also look at various aspects of long-term sustainability of the technology,” says Zaman.

“The problem with counterfeit and substandard medicines in the developing world is so vast that we need a disruptive innovation like PharmaChk to stem the tide,” said Wendy Taylor, director of USAID’s Center for Accelerating Innovation and Impact. “We’re excited about how well this device is performing in early field testing and are hopeful that PharmaChk can be a real game changer for detecting poor quality medicines and preventing their spread and use.”

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.