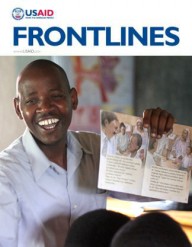

Teacher Beatha Nikuze interacts with students in her third grade classroom at Kanyinya Primary School in Rwanda’s Southern province.

Amber Lucero-Dwyer, USAID

Teacher Beatha Nikuze interacts with students in her third grade classroom at Kanyinya Primary School in Rwanda’s Southern province.

Amber Lucero-Dwyer, USAID

Teacher Beatha Nikuze interacts with students in her third grade classroom at Kanyinya Primary School in Rwanda’s Southern province.

Amber Lucero-Dwyer, USAID

Teacher Beatha Nikuze interacts with students in her third grade classroom at Kanyinya Primary School in Rwanda’s Southern province.

Amber Lucero-Dwyer, USAID

Recent years have brought Africa into a new age of development, and Rwanda is considered among the continent’s star performers.

However, the literacy rates in the country remain too low—65.9 percent among adults, 77 percent among youth—for the officials whose goal is to see the country reach middle income status by 2020. A culture of reading is absent. But that is starting to change.

To help Rwanda create a reading environment, early primary classrooms now have access to a variety of children’s stories through USAID’s All Children Reading: A Grand Challenge for Development.

In 2012, Drakkar Ltd., a local publishing company, received an All Children Reading grant to reproduce high-quality stories by African authors. To date, six titles have been translated into the local language, Kinyarwanda, and distributed to 240 schools in three districts—that comes out to about 221,000 students. Starting in first grade, teachers read the stories aloud to classrooms.

One of the participating schools is Kanyinya Primary School in Ruhango district in Rwanda’s Southern province, about two hours outside the capital city of Kigali. Like many other rural schools in Rwanda, Kanyinya had limited access to quality reading materials. Before joining the program, storybooks at the school were few and did not appeal to children. Teachers did not know how to use them in the classroom or how to excite children about reading.

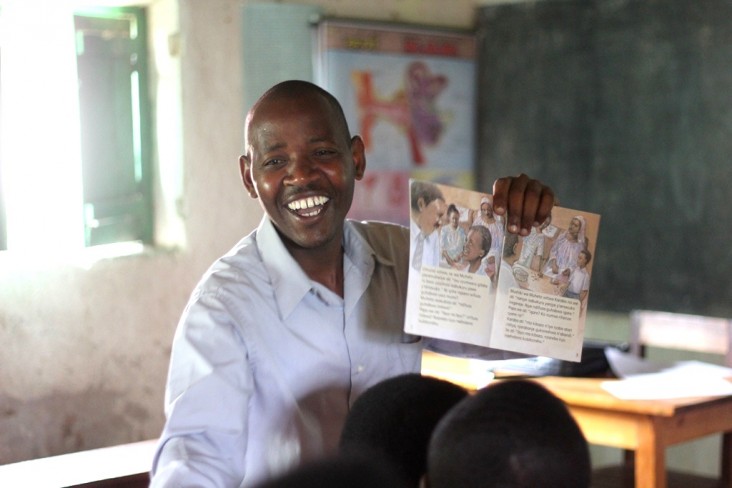

At Kanyinya, teacher Beatha Nikuze uses the books in her Kinyarwanda third grade lessons. She and her colleagues learned from mentors at her school how to read the stories with expression and animation, changing their voices for different characters or when the story reaches an exciting point, engaging the students in the story.

“I try to mimic the characters’ voices,” says Nikuze. “If it’s a child’s, I make a child voice, if it is a cow, I make a cow’s voice …. Children like that. They laugh at me, at the same time learning. I like that too.”

Nikuze walks around the classroom with the book so that all children can see the pictures. Reading stories in this way has had a big impact on students’ attitudes about reading.

“Before, [the children] did not have much interest in reading,” she says. “But things have changed. Now everyone wants to read a book.”

“Happy the Street Child” is a favorite among the children at Kanyinya. In the story, Happy is a young girl who has lost her family and finds herself living on the street. Her old childhood friend Umutoni discovers her one day on her way to school. Umutoni talks to Happy and defends her when the other children mock her.

“What matters is that she is a person just like us,” Umutoni tells them. “The only difference is that she has no one to take care of her.” After Umutoni presents the idea to her parents, Happy moves in with the family and returns to school, becoming first in her class and earning a place at the best secondary school after excelling in her primary examinations.

“I like that Happy was sent to school,” said third grade student Jean Claude Nsengiyumva.

“The story teaches us a good lesson,” added Prince Kwizera, a classmate. “My favorite character in the story is the student [Umutoni], because she is the one who helped Happy.”

In addition to developing a love of stories, children also learn the structure of a story—that it has a beginning, middle and end, and usually includes a problem to be solved. Mentors support teachers to help children re-tell or draw stories, make connections between the stories and their own lives, and predict what may happen next in the story. These strategies help children develop comprehension skills.

Many children connect with “Happy the Street Child.” “The story describes what they know,” says Nikuze. “Some of these children experienced the same things. It gives them hope that maybe life can change.”

When Nikuze reads this story, she asks the children if they know any children like Happy or whether they too have ever worried about succeeding in school. She likes to give students time to think on their own before letting them discuss their ideas with a partner. Then they share with the class.

“I like the teacher asking us questions and answering these questions,” says Jean Claude, one of her students.

“With this method, everyone is active,” says Nikuze. “Everyone is engaged in the lesson.”

Building Blocks of Early Literacy

The challenge of literacy is a complex one in Rwanda, especially with the 2009 transition from French to English as the primary language of instruction.

To address the wider issues of basic literacy and numeracy, USAID also supports literacy development through its Literacy, Language and Learning (L3) Initiative implemented by Education Development Center. The project develops a complete package of instructional materials to support and enhance the curriculum, including stories for teachers to read aloud. Embedded in the stories are the letters, grammar or other language elements that students study in a given week.

Audio recordings of the stories, which teachers play using ordinary cell phones, allow teachers to move around the classroom, ensuring that all children have the chance to follow along and see the pictures in the book. In all corners of Rwanda, urban and rural, the use of cell phones and other technologies is widespread and increasing, expanding the possibilities for reaching communities and classrooms with literacy materials in new, innovative ways.

“Working together with the Ministry of Education to promote quality education in Rwanda’s primary schools is one of the cornerstones of the U.S. Government’s work in Rwanda,” said Susan Bruckner, director of USAID/Rwanda’s Education Office. “Literacy is the foundation of learning and future prosperity, and the innovative materials we are collaboratively developing are the essential building blocks of early literacy. They are full of rich content and include proven methodologies that are exciting for both teachers and students to use.”

These investments in quality primary education are just part of the work the country plans as it works to build human and infrastructure resources to transition from an agricultural-based economy to a knowledge-based one, and aims to become a regional information and communications technology hub on the continent.

Readers Becoming Writers

USAID also is partnering with Rwanda’s Ministry of Education to hold a national competition for writing children’s stories and poems called Andika Rwanda, or Rwanda Writes. All Rwandans, from first grade and up, were eligible to participate. Writing took place from February to May, and this summer, the ministry will announce the winners, who will come to Kigali for awards, which include professional publication and illustration of their story and writing tools like tablets and laptops.

“Andika Rwanda fits into the overall picture of Rwanda because today our emphasis, both from the Ministry of Education perspective and from the government perspective, is improving the quality of education. It is priority number one,” says John Rutayisire, director general of the Rwanda Education Board under the Ministry of Education.

At the end of the competition, each primary school will receive a published volume of the winning entries, and teachers will be encouraged to read them to their classes. Included will be 12 new and original Rwandan-authored stories and poems, four of them written by primary students.

Emmanuel Habimana, an eighth grade student at Mushubi School in Nyamagabe district, wrote a story for the competition. As a primary student, he recalls enjoying well-known Rwandan stories and thought that he could write a new story that primary school children might enjoy.

“I have brothers and sisters in primary school,” he says. “I read them [my] story and they liked it. I told them not only to laugh but also to learn from it.”

“Primary kids reading these stories may feel confident to write stories,” adds Emmanuel. “They may even say: ‘If he can write this story, why not me?’”

Jackie Lewis is with the Education Development Center. Justin Smith is with Drakkar Ltd.

These Kids Can Read!

By Christine Beggs, Rina Dhalla, Shibi Jose and Fabiola Lopez-Minatchy

In 450 villages across Maharashtra, India, children participate in six-day, two-hour, intensive summer learning camps run by Pratham Education Foundation. This local organization, awarded a grant under USAID’s All Children Reading: A Grand Challenge for Development, aims to change the education trajectory of India.

India is the world’s most populous country with a third of the population under age 15. In 2009, the government enacted the Right to Education Act, which calls for free and compulsory education for all children ages 6 to 14 years. The national net enrollment rate has reached 96 percent at the primary level, and 99 percent of all communities have a primary school located within one 1 kilometer from their communities. Despite these improvements, large pockets of the school-age population are not reading at grade level or with enough proficiency to learn effectively. Pratham’s 2013 Annual Status of Education Report noted that over half of grade five students could not read a grade two Hindi text.

But Pratham’s CEO Madhav Chavan has a vision: “For these schools, and all over India, we believe skill-based learning camps can turn around a whole school from non-reading to reading.” Based on the camps visited by USAID in Maharashtra, this vision is turning into reality—these kids are reading and they are reading with comprehension and imagination.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.