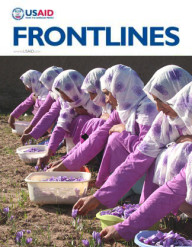

USAID partner Focus Humanitarian Assistance trains women leaders to serve as first responders as part of disaster risk reduction training in Balkh province.

Save the Children/Zubair Shairzay

USAID partner Focus Humanitarian Assistance trains women leaders to serve as first responders as part of disaster risk reduction training in Balkh province.

Save the Children/Zubair Shairzay

USAID partner Focus Humanitarian Assistance trains women leaders to serve as first responders as part of disaster risk reduction training in Balkh province.

Save the Children/Zubair Shairzay

USAID partner Focus Humanitarian Assistance trains women leaders to serve as first responders as part of disaster risk reduction training in Balkh province.

Save the Children/Zubair Shairzay

Under the Taliban, virtually no girls attended school, and women were unable to voice their opinions, could not earn an income, leave their houses or live their own lives. Now, women have seized opportunities in every sector of Afghan society, from the classroom to the growing private sector and the political area. However, much remains to be done.

Adisa Busuladzic, a USAID development and outreach communications officer, recently sat down with gender advisers Fazel Rahim, Nicole Malick and Dr. Alia El Mohandes to discuss the strides the women of Afghanistan have made in the past 12 years and what the future holds.

FrontLines: What drew you to specialize in gender with USAID?

Fazel Rahim: My mother had always dreamed of sending me to law school so I could assist my youngest aunt, who was forced into marriage at the age of 12 to an older relative. The domestic violence started as early as her wedding night and continued with regular, brutal beatings. The tradition of safeguarding family reputation prevented her from asking for help. I witnessed this silent violence throughout my childhood. While her husband was busy courting a second wife, my aunt was diagnosed with cancer. Her husband would not allow her to stay in her own home and refused to pay her medical costs.

I decided to become a defense lawyer to help women like my aunt. I graduated from law school in 2007 and worked as a legal counselor for imprisoned women and as a program manager for an NGO. After years of studying, I was finally able to represent my aunt in divorce proceedings. After a six-month legal battle, her divorce was finally granted. Since then, I have focused my energies on women’s empowerment.

Nicole Malick: I was in Kandahar coordinating aid with the international troop contingent in the area. It was clear that, to make a lasting impact on the well-being of women, we had to do more than arrange sporadic meetings with local women—as that meant we were serving more as passing curiosities than as agents of change. In Kandahar, women’s participation in society and their ability to move within their own communities was tenuous. By the time I left Kandahar, our impact was palpable. Older generations began encouraging their daughters and sisters to stretch the traditional boundaries that had enclosed them. The commitment I saw firsthand of both Afghan and ISAF [International Security Assistance Force] women to greater equality drives me to continue this work.

Alia El Mohandes: Growing up in Egypt, I was exposed to the shifting values that governed gender in the Middle East through the political turmoil of the 70s and 80s. I joined Save the Children USA as they were setting up their first office in Egypt and developed their first strategy for an integrated health and women’s program. My work there drove me to pursue my interest in gender equality throughout the Middle East and Africa ... and now Afghanistan.

FrontLines: Is the traditional perception of Afghan women in the United States flawed?

Nicole Malick: When the international community sees Afghan women in pictures and on news reports, they are distracted by faceless blue burqas, seemingly devoid of personality or volition. But underneath those billowing garments are strong mothers, sisters and friends. Many of those women remind me of former colleagues and family back in the United States.

The tremendous level of interconnectivity between women, both within and between villages and families, is often invisible. Even if a woman does not own a cell phone of her own, her husband or brother or cousin does … and she’ll use it. Women now spread the word about events using mobile phones, and they use social media to express themselves. This is a massive shift from even a few years ago. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, 80 percent of Afghan women had access to mobile phones in 2013.

Alia El Mohandes: Americans tend to equate equality with a demand that women be the same as men. In other regions of the world, a more common perception asserts that femininity does not exclude roles in public life. These women take pride in being women, mothers and wives while at the same time holding ambitious career goals. We focus on ensuring that girls and women in Afghanistan have the same opportunities and choices as men and boys do, and that they have the right to live secure and dignified lives.

FrontLines: What do you consider to be the most striking similarities and differences between the state of gender equality in Egypt and Afghanistan?

El Mohandes: Egypt is a test case of how women’s empowerment is a continuous battle. The emancipation of Egyptian women started in the 20s and 30s with the famous Egyptian feminist Hoda Shaarawi’s decision to unveil in public. Egyptian women have seized opportunities to gain education and income. By the time I attended medical school in Egypt, the student population was 50/50 male to female.

Gender equality in Egypt suffered setbacks in the 80s with the rise of conservatives. Women who had once experienced freedom retreated back to their homes and stopped participating in civil society and political discourse. Yet in the last two to three years, a new wave of feminism rushed forth with the Arab Spring and many women are reclaiming their places in society and the economy. To me, Afghanistan is approximately where Egypt was in the early 20th century.

FrontLines: What is the role of men in empowering Afghan women?

Rahim: In all of these conversations about gender, we leave out half of the population of the world. In 2002, almost no girls were attending school in Afghanistan. Today, nearly 40 percent of pupils are girls. Ask yourself this question: In a patriarchal society, who is it that you need to convince that the proper place for girls should be in the classroom? Men play an integral role in empowering their mothers, their sisters, their wives, their daughters.

FrontLines: What is the one deciding factor in achieving gender equality in Afghanistan?

Rahim: It all goes back to that exhausted cliché, “It’s the economy, stupid.” When women gain access to economic resources, when they are the ones bringing income into their households, they become equal to their fathers and husbands.

El Mohandes: Without access to education, the door will never open to economic opportunity. The first verse in the Quran is telling; it asks ALL to read and seek knowledge.

Malick: Education and economic opportunity go hand-in-hand. When USAID first started working here, Afghan women in rural areas overwhelmingly called for basic literacy and technical skill training. Now, if you speak to Afghan women, they are calling for government accountability, coalition building and marketing and business development training.

Rahim: That’s why USAID’s gender initiatives in Afghanistan are now focusing on widening access to quality education and training for promising young women who are on the verge of starting careers. Only when the women of Afghanistan have the power to make decisions can the girls of Afghanistan dream of a different future. Our new program Promote, the largest gender program in USAID history, is designed to accomplish this. By providing opportunities for 75,000 educated women to enter into leadership positions, we think we can make the gains Afghan women have made irreversible.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.