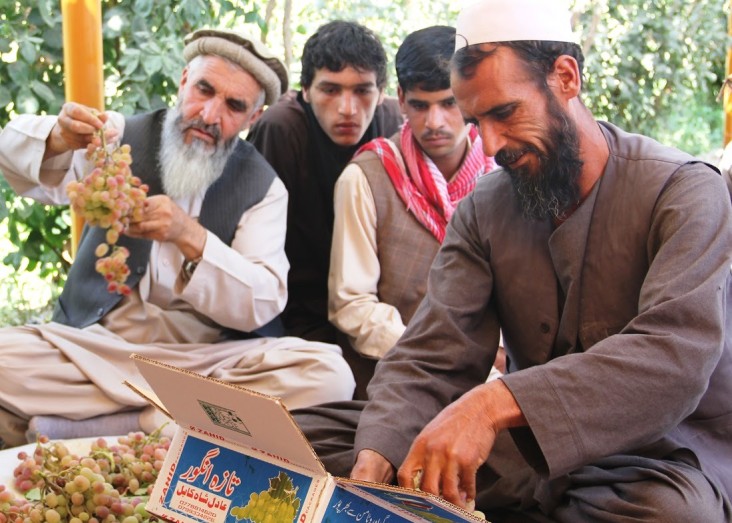

Mohammad Nasir, a farmer from Parwan province, Afghanistan, inspects his nearly ripened grapes.

USAID

Mohammad Nasir, a farmer from Parwan province, Afghanistan, inspects his nearly ripened grapes.

USAID

Mohammad Nasir, a farmer from Parwan province, Afghanistan, inspects his nearly ripened grapes.

USAID

Mohammad Nasir, a farmer from Parwan province, Afghanistan, inspects his nearly ripened grapes.

USAID

Strips of rusting tank treads cut across the dusty road leading into the village of Charikar, just an hour’s drive from Kabul. The treads act as speed bumps to deter would-be speeders, while also reminding villagers of the Soviet invasion that brought an abrupt halt to agricultural production in the once-thriving Parwan province back in the 1980s.

Mohammad Nasir grew up in Charikar. Walking through his 2-hectare farm, the gray-bearded, 72-year-old farmer points to crumbling buildings and fallen mud-brick walls. “These were built by my ancestors,” he said. “Times were good then. We grew grapes, cotton and wheat, and we hired 10 local men to work on the farm.”

Unfortunately for Nasir, his farm has been on the frontlines for more than two decades of fighting. When a mujahidin-fired rocket destroyed his home and killed several of his workers, he had to cut down his trees and sell them as firewood to move his family somewhere safer. The family later returned to their farm, only to have the Taliban destroy the irrigation to all of Charikar, turning farmland into dustbowls. Nasir and his family were reduced to begging to feed themselves.

Today, Nasir is back on his land and the proud owner of a prospering grape vineyard, which has been in active production for the past three years. He is bringing in more income than ever, and he expects to soon put another parcel of land into production. He credits the USAID Commercial Horticulture and Agricultural Marketing Program (CHAMP) for getting him back on his feet. USAID provided him with grape saplings, technical assistance and advanced trellising systems to increase both the output and quality of his grapes.

While most in the region grow their grapes the traditional way, on earthen mounds, Nasir’s vines climb across wires suspended from tall concrete posts like clotheslines. Unlike his neighbors’ grapes, which are grown close to the ground and must contend with moisture and pests, Nasir’s trellised vines expose the grapes to more sunlight and airflow, encouraging growth and increasing the quality of the grapes.

Nasir’s grape yields have nearly doubled. The plump green bushels from his vineyard are now export-quality, allowing him to sell his grapes at a higher price than he could fetch in local markets. Before trellising, his vineyard was producing around 2,500 kilograms per jerib (about one-fifth of a hectare). This year his yield was 4,900 kilograms per jerib.

“The neighbors thought I was making a big mistake, that the grapes would be damaged by the wind,” he said. “But now they want trellises for their own vineyards.”

With the income Nasir received from last year’s harvest, he sent his grandchildren to school. This year he plans to construct a high wall to protect his grapes and his now-famous trellises.

Nasir’s 40-year-old son Mahmoud quit his job as a local schoolteacher so he could help out full time on the farm. He said, “[The neighbors] come around at night and dig the posts right out of the ground. First they laughed at us, now they envy us for our success.”

A Proud Agricultural Past

Afghanistan’s economy depends overwhelmingly on agriculture. While 88 percent of the country is too mountainous, arid or remote for any large-scale commercial farming, a majority of Afghan families depend on farming or livestock rearing as their primary source of income.

Prior to the wars that decimated the country, Afghan pomegranates, raisins, apricots and dried fruits were known the world over, the cool summers and dry climate being ideal for orchards. From its strategic location along the famous Silk Road, Afghanistan exported more than 60 percent of agricultural products to lucrative markets in South Asia, the Middle East, Europe and the former Soviet Union.

Since 2002, USAID has been helping Afghan farmers put their land back into production. Now, USAID’s $40 million CHAMP program is working with farmers and agribusinesses to bring their products up to international standards and to help them to rediscover and find new markets. Slowly but surely, Afghan produce is finding its way back onto supermarket shelves in countries like India, Pakistan and the UAE.

CHAMP increases the value of Afghan produce by applying a field-to-fork approach, concentrating on products with strong export potential like almonds, apples, apricots, grapes, pomegranates and melons. CHAMP works with Afghan businessmen along the entire agricultural value chain—from the farmer and the local trader to the warehouse owner, shipper and international buyer—to increase quality and efficiency.

To receive CHAMP funding, business owners must invest in making improvements, which can range from using better seeds and growing technologies on farms to introducing refrigerated storage and modern fruit packaging machines at agribusinesses. Typically, the Afghan business will invest 25 to 30 percent of the total value of the improvements, with USAID covering the remainder.

“There is a huge market for Afghan produce in the Indian sub-continent, Southeast Asia and the United Arab Emirates,” said Abhey Misra, an Indian buyer of Afghan raisins. “Afghanistan has improved its standards of quality and packaging. It has a good reputation and their products are known for being 100 percent organic.”

CHAMP operates in half of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces and nearly 100,000 Afghan farmers and traders have already benefited from the program. More than 23,000 metric tons of fresh and dried fruit exports have been facilitated by CHAMP in just the past two years. This has enabled program participants to see an increase of nearly $20 million in annual income over the previous year.

At the 2014 Gulfood Exhibition in Dubai, the world’s biggest food fair, Afghanistan exports were on display for tens of thousands of buyers from around the world. CHAMP brought 21 Afghan traders to participate at the exhibition, nearly half of them women. These exhibitors signed more than $8 million in deals for Afghan fruits, nuts, saffron and juices.

Haji Sharif, vice president of Almosaneer Co. in Saudi Arabia, signed a $400,000 contract for Afghan raisins. “When I saw Afghans here, I was proud to know that Afghanistan is back on the world stage,” he said. “In Saudi Arabia: Arabs, Pakistanis, Indian people, everyone wants Afghan dried fruit and nuts!”

More Work To Be Done

Nasir’s grapes are still an exception. Barriers to trade often prevent Afghan products from getting out of the country and exports are growing only slowly, according to the World Bank. Challenges range from the inability of Afghan trucks to cross into Pakistan to power problems to a lack of internationally accredited food certification, which makes lucrative markets in the United States and European Union inaccessible.

USAID is helping to develop and extend more productive agricultural practices to farmers; improve their access to training, information, markets and credit; and energize the private sector to recognize that it is in their own interest to provide farmers with more and better services and inputs (like seeds, saplings, fertilizer and livestock breeds). U.S. assistance has also included rehabilitating irrigation canals, sponsoring agro-trade conferences and purchasing modern farming equipment. Since 2002, USAID has invested at least $1.9 billion in Afghan agriculture.

“Afghanistan has come a long way,” said Gary Kuhn, president of Roots of Peace, the California-based organization that runs CHAMP. “A few years ago, exporters couldn’t find enough quality fruit that was ready for international buyers. That’s no longer such a big issue. Afghan farmers are producing better fruit, thanks to years of USAID-funded efforts like CHAMP. The challenge now is getting that fruit onto supermarket shelves around the world.”

But Kuhn is optimistic, as is Mohammad Nasir, the Parwan grape farmer.

“I was skeptical about CHAMP,” Nasir says. “We all question new things, but when you see the results, you must learn to have faith that good things can happen in life.”

As he spoke, Nasir raised a water bottle to parched lips and moved toward the shade of his grapevines. “On this spot, I saw men killed in a rocket attack,” he said. “I could have given up, but I built this vineyard so that my children would have a better life than I have had. The children are in school and the vineyard is producing. It gives us hope.”

Will Everett is with Roots of Peace.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.