Midwife Friba Hashimi attends to a patient.

Futures Group/Afghanistan

Midwife Friba Hashimi attends to a patient.

Futures Group/Afghanistan

Midwife Friba Hashimi attends to a patient.

Futures Group/Afghanistan

Midwife Friba Hashimi attends to a patient.

Futures Group/Afghanistan

Friba Hashimi brings Afghan babies into the world. She works as a midwife in the eastern reaches of Bamyan province, a part of the country where childbirth is often potentially life-threatening for infants and mothers alike.

Hashimi said that her specialization—making childbirth safe for some of Afghanistan’s least advantaged women—was unimaginable just a few years ago.

“It was very rare for families in my district to allow women just to go outside their homes, yet enough to go and attend training,” Hashimi said.

In 2002, Afghanistan had one of the highest rates of maternal and child mortality in the world due to a dearth of basic health care, equipment and facilities. Improved Afghan Government public health policy and international assistance—in which USAID has played a leading role—have helped reverse these rates by educating women like Hashimi. Afghanistan’s current maternal mortality rate is 327 per 100,000, a drastic improvement from the Taliban years when the rate was 1,600 per 100,000 births.

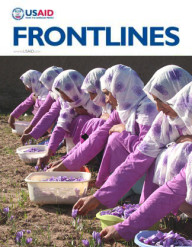

Over the past decade, the international community has partnered with Afghanistan’s Ministry of Public Health to train women like Hashimi to respond to life-threatening complications during childbirth like severe bleeding and infections. In addition to teaching basic techniques and conventional knowledge, students have learned how to navigate “Afghanistan-specific” issues like the shortage of trained physicians, a cultural tradition of never discussing intimate matters with non-family members, and dealing with sometimes impassible terrain separating midwives from mothers-to-be.

Through 2013, more than 4,000 Afghan women from all over the country were trained to be midwives, with USAID providing the training for almost half. Hashimi was one of the very first.

“A Better Solution”

During a break from her work, Hashimi said she had always been fascinated by the doctors and nurses she observed during childhood visits to the local hospital. Her inquisitive eyes followed the medical staff as they hurriedly went up and down the hallways doing their rounds, providing treatment and conversing with patients. She eventually got a chance to help out in a local vaccination initiative, but Hashimi never thought that a medical career was even a remotely feasible option.

Giving birth to her own two children made Hashimi realize what she really wanted to do. The experience made her acutely conscious of the indignities pregnant women often endured in her area, in many cases because of the sheer distance between her village and the hospital. She recalled that it was not uncommon for women to die along the side of the road in desperate attempts to get to medical facilities for help.

“It was obvious there had to be a better solution,” Hashimi said. “Our community needed it.”

When Hashimi heard that a Community Midwifery Education program was coming to her province for the first time, she immediately applied to take part. It was not easy; she already had two children at home and then there were the traditional village customs which prohibited girls and women from traveling for any reason, even to attend school.

Hashimi’s response was typically Afghan—she turned to her relatives for support. Her family moved from Ghajorak to the center of Bamyan province, about an hour and half away, to allow her to attend the training. Her husband gave up his job as a community health officer and, while his wife studied, he took care of the children.

The intensive course lasted 18 months. Upon graduation, Hashimi moved back to her home district to serve as a community midwife. She became the only female health caregiver at the local clinic. In some cases, her patients were receiving conventional health care for the first time. Hashimi is convinced that this simple step—providing basic health care to people who never had it before—saved lives.

“I provided antenatal care and tried to raise awareness among families about pregnancy-related emergencies,” she said. “Soon enough, I began to identify early warning signs in pregnancies and referred patients before life-threatening complications could arise.”

The midwife job, initially paid for with USAID funding and now supported by the Agha Khan Development network, was not just morally rewarding. Being a midwife allowed Hashimi to help support her family. In due time, she was also promoted to be a trainer in the midwifery school. Today, few babies come into the world in Ghajorak without her knowledge. Usually, she is the midwife that handles the delivery. Hashimi has become one of the most respected and sought-after government workers in her entire village, male or female.

Saving New Lives

“Supporting the ambitions of women like Friba Hashimi has yielded results. Ten years ago, there were less than 50 midwives in all of Afghanistan. Now there are thousands,” said Xerses Sidhwa, a USAID health team leader.

Zahr Mirzaee, a midwife in Sari-Pul province, described what an exponential increase in midwife numbers meant in her district of 532,000 people.

“There was one female provider, a nurse, in the provincial hospital of Sari-Pul in 2003,” Mirzaee said. “Now community midwives are available in most clinics and are providing much needed support to women in their communities by assisting deliveries and stabilizing and referring complicated cases.”

Gul Bibi, a Sari-Pul mother of four, echoed the importance of having access to the kind of expertise trained midwifes like Hashimi provide: “I am very pleased that we have a midwife in our village, and we can access her all the day and night. We can share our health issues and get her consultation.”

Midwives and mothers agree childbirth in Afghanistan is still too dangerous. Though the numbers have improved dramatically over the last decade, the country’s infant and maternal mortality statistics are far from rates in developed nations.

“The collaboration between our governments will remain strong as Afghanistan expands on the gains made for women and increases access to health care for all,” said Sidhwa. “As the government begins to pay for more of its health care delivery and its institutional and personnel capacity builds at all levels, we can expect great things from Afghanistan. Women and children will be healthier and the population as a whole will live longer.”

Across Afghanistan, thousands of women like Hashimi are bringing children into the world safely in villages and districts where, previously, a new mother was on her own when giving birth.

As Hashimi considered how her life had transformed since her first day of class, she can’t help but smile. “My education as a midwife has changed my life dramatically. It enabled me to support women of my country and save their lives—and the lives of their babies.”

Omarzaman Sayedi is chief of party for USAID’s Health Policy Project in Afghanistan. Mursal Musawi is executive director of the Afghan Midwives Association.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.