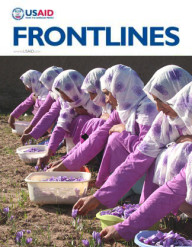

Members of the Ghoryan Women’s Saffron Association pick flowers during the saffron harvest.

USAID

Members of the Ghoryan Women’s Saffron Association pick flowers during the saffron harvest.

USAID

Members of the Ghoryan Women’s Saffron Association pick flowers during the saffron harvest.

USAID

Members of the Ghoryan Women’s Saffron Association pick flowers during the saffron harvest.

USAID

Since the United States returned to Afghanistan in late 2001, USAID staff has been on the front lines to support overall U.S. Government objectives and to propel development gains in a country hit by decades of civil war. I have been fortunate enough to be mission director in Afghanistan for the past 14 months, and plan to serve a second year.

We all know that 2014 is a year of transition. We have seen a major security transition with the withdrawal of many of our troops as the military moves into their “train, advise and assist” mission and Afghan security forces take on responsibility for their own security. It has also been a year of political transition with the election of a new president after 10-plus years of President Hamid Karzai. The elections have required extraordinary USAID involvement with the 100 percent audit of all ballot boxes, unprecedented in other countries around the world. This year represents a year of economic transition, with the decreasing role and spending from the international community, especially related to the military drawdown. Finally, 2014 is a year of staffing transition as we decrease our U.S. direct hire staffing levels by hundreds and we hire and train new foreign service national staff.

Afghanistan remains a very difficult place to work for USAID, but opportunities for development impact abound. U.S. Government civilians, including those working in diplomacy and development, are playing an increasingly vital and urgent role in supporting Afghanistan’s move towards peace, security and development. In concert with other parts of the U.S. Government, USAID has developed a 10-year strategic vision paper for the so-called Afghanistan Decade of Transformation as well as a three-year strategic plan with a clear roadmap of priorities and expected results. Our strategic objectives include: maintaining and expanding the incredible gains that the Afghan people have shown in the past 10 years in health, education and women’s empowerment; expanding economic growth, mainly through agriculture; and helping Afghanistan continue to improve governance, from democratic elections to sub-national governance to support for media and civil society.

In fact, in November we launched the Agency’s largest gender program, called Promote. It reinforces our undeniable commitment to seeing gender empowerment across society here take hold, and, we believe it will become a model for other gender programs. USAID’s mission in Afghanistan remains the Agency’s largest mission in the world. Despite continued insecurity and uncertainty, our implementing partners and all Afghan counterparts in government and in the private and non-government arenas remain incredibly focused and committed to continue a vital development program. We are putting in place a robust multi-tiered monitoring program to ensure that USAID can fully maintain its required oversight, management and fiduciary responsibilities.

We are excited about the future with the inauguration of a new president and government with a clear vision of needed reforms. Two rounds of an election saw millions of Afghans, one-third of whom were women, risking their lives to vote and to have a say in their country’s future direction.

Our impression is that Afghans, especially the youth, want change within traditional norms, and appreciate health services and education for their children. We are moving away from the quick-response, quick-impact programs of the past decade to more traditional, evidence-based development programs, embracing a long-term vision and supporting “strategic patience.” We have a saying in Kabul: This is a marathon and not a sprint.

Recent data from years of stabilization programs will no doubt inform future Agency programs. With the largest USAID government-to-government program in the world, our experience and mistakes inform and caution the Agency. I expect that our broad multi-tiered monitoring strategy will serve as a best practice of interest to USAID missions in other post-conflict and non-permissive environments.

Finally, I want to say a word about the incredible work and sacrifices of our staffers—both past and current. I realize that many hundreds of USAID officers now serving in missions around the world have served in Afghanistan over the years, and I continually welcome USAID staff returning to Kabul for a second or third tour. We also host some 40 third-country nationals from USAID missions around the world, carrying out key functions in the mission. Your work has been essential in helping build a strong foundation from which the Afghan people can rise.

Lessons Learned in Afghanistan

“People construct this dichotomy that development goals are somehow different from national security or stabilization goals, and I don't buy it. I actually think that, in general, what is in the best interest of development is also in the best interest of effective stabilization.”—Alex Thier, assistant to the administrator, Office of Afghanistan and Pakistan Affairs (2010-2013)

“It is inevitable that you will make some mistakes while doing development work. Making a mistake once is part of the learning process, but repeating a mistake is simply unacceptable.”—Donald “Larry” Sampler, assistant to the administrator, Office of Afghanistan and Pakistan Affairs (2013-present)

“One key to improving USAID’s ability to deliver in a war zone is finding the proper balance between short-term results and long-term development. It can’t be an either-or scenario. It has got to be such that, whenever we look for the short-term gains, we also ask ourselves up front if these short-term efforts could support or undermine the long -term gains we are after.”—Michael Yates, USAID/Afghanistan mission director (2008-2009)

“I do not think we have learned how to manage the fundamental tension between the need for fiscal oversight and the need to act quickly in a war-time situation. Nor have we found a way—with Congress or inspectors—to use mistakes as a way to learn rather than blame. The result is to reinforce a bureaucratic culture that puts risk minimizing well above any other goals.”—Ambassador Ronald Neumann, U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan (2005-2007)

“I think that in terms of lessons I learned, one is the importance of monitoring, especially in that kind of environment where your mobility is limited. Sometimes building a bad project can be more damaging than building no project at all. And so ensuring quality control—mostly through direct monitoring—is crucial. We actually improved our ability to do this, but it took us a while.”—Patrick Fine, USAID/Afghanistan mission director (2004-2005)

“What worked best was when we were working hand in hand with the military. We were both in error of not understanding one another’s interest in the short term and the long term, but closer coordination in the field overcame these differences better than did endless office discussions.”—Robin Philips, USAID/Afghanistan mission director (2007)

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.