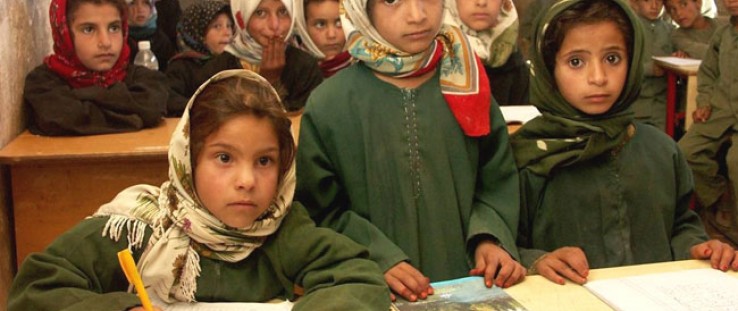

School girls in Sana’a.

Clinton Doggett, USAID

School girls in Sana’a.

Clinton Doggett, USAID

School girls in Sana’a.

Clinton Doggett, USAID

School girls in Sana’a.

Clinton Doggett, USAID

SANA’A—Yemen has a severe literacy problem.

Nearly half of the population is illiterate. In some regions, 60 percent of the residents never learn to read, and among women, the rate can reach as high as 80 percent in certain outlying areas.

Many Yemenis only learn to read in the later elementary grades—at times as late as sixth grade, if at all. Making the problem more urgent, three-quarters of Yemen’s population is 25 years old or younger. Educating tomorrow’s future leaders has a special urgency for the country in transition.

In 2011, young people throughout the country led the call for a new Yemen that culminated in the election of a new president in February 2012, after 33 years of authoritarian rule. Today, Yemen has a new transitional, democratic government working actively to lay the foundation for that better future, and doing so in a more accountable and transparent way.

The transitional government understands that building a prosperous, modern state must begin with its young people and especially its girls. In 2008, only two-thirds of girls were enrolled in primary school, and less than half of them graduated. In contrast, 83 percent of boys were enrolled and more than two-thirds graduated. Unlocking Yemen’s full potential begins with closing this glaring opportunity gap.

The government has made some progress in improving the country’s education system, but challenges persist: low school completion rates by girls, especially those in rural areas; high grade-repetition rates; and a lack of quality facilities and materials, particularly in vulnerable communities.

USAID is helping the government to improve teaching practices in primary schools and to build or rehabilitate school infrastructure so that students, particularly girls, want to stay in school.

“A better education system can help lay the groundwork for a more successful Yemen by improving the reading abilities of children in first through third grades, which is considered a strong predictor of future success in school, and providing girls an equal opportunity to learn,” explained USAID/Yemen Mission Director Robert Wilson. “Reconditioning schools’ basic infrastructure also is important for a conducive learning environment that is fully accessible for girls in Yemen, where it is particularly important that parents are comfortable sending their daughters to school with appropriate physical structures.”

Helping Teachers Teach

The Yemeni Government is committed to improving the educational system and USAID is providing critical support. At least 3,500 school teachers, principals and inspectors from schools in Sana’a and Taiz governorates—two of Yemen’s more populated regions—are improving the reading skills of Yemen’s youngest students, with strategies acquired from successful USAID-supported programs.

USAID developed the Early Grade Reading workshop, which is changing the way teachers help students learn. During a six-day period in early May, the educators participated in workshops throughout Taiz and Sana’a. They developed new skills designed to help improve the reading abilities of almost 124,000 Yemeni students in first through third grades.

Traditional methods of education in Yemen center on rote memorization and lectures. In both, one-directional communication is used: Once teachers provide information to their students, the learning process is considered complete. Too often, students are not taught how to analyze or practically apply newly acquired information.

In the workshops, the educators learned about student-centered, interactive learning; the importance of assessing children’s reading skills and providing feedback; and the need for parent involvement in the learning process.

Magide Ahmad, a third-grade teacher at the Al Yarmouk School in Sana’a, has taught elementary school students for 18 years. She said she had heard of interactive learning, but always thought its purpose was to give teachers a break from the grind of constantly providing information to students rather than to more effectively help children learn.

“Before the [USAID] workshop, there was very little interaction between the students and me, but now I know why I need to make my class more interactive and interesting,” said Ahmad. Today, Ahmad provides audio tapes for her pupils so they understand proper phonetic pronunciation, and the children draw posters that reflect the stories they read.

For 80 percent of the workshop participants, many of whom have teaching careers spanning 20 years, this was the first professional training they had ever received. The workshop was designed to allow teachers to begin using their new skills hours after they learn them. In many cases, the teachers attended the workshop during the first half of the day and were back in the classroom in the afternoon.

“The best part of this training was that we were able to practice immediately what we had learned,” said Ibrahim Saleh Al-Dhaibani, a teacher from Taiz. “This training gave me more self-confidence in my interaction with my students and it enriched my knowledge and skills.”

By the time the initiative is completed, it is expected to involve 10,000 teachers and affect 300,000 children throughout Yemen. Impressed by the quality of the program’s methodology, Yemeni Ministry of Education officials say they now plan to replicate the approach throughout the country.

Safety in Better Schoolhouses

USAID also is placing an emphasis on improving the infrastructure of schools and classrooms in Yemen, because safer facilities are shown to increase enrollment and reduce dropout rates, especially for girls. Whereas boys in Yemen tend to drop out when their families need economic support, parents will hold back their daughters if they perceive that schools are not providing the protective environment expected in Yemeni society. Parents have less reason to keep their daughters at home when schools provide adequate security, such as separate classrooms, recreation rooms and bathrooms for girls and boys.

USAID is supporting the Ministry of Education by helping to provide tailored maintenance, infrastructure, service upgrade and repair work to 140 schools across eight governorates of Yemen. More than 140,000 students—including 65,000 girls—are expected to attend these schools.

Among those students are 2,000 girls at the newly refurbished Al-Jeel Al-Jadeed School in Sana’a. The overcrowded primary and secondary girls’ school, where students attend classes in two shifts, had been neglected for years. One of the oldest schools in Sana’a, it was built nearly 50 years ago but has never been maintained sufficiently, especially in recent years.

“The dirty, boarded up walls and windows used to distract my attention,” said Samah Al-Amrani, a 12th grade student at Al-Jeel Al-Jadeed School.

Last month, USAID project staff responded to a request by Yemen’s Ministry of Education to refurbish the school. Damaged walls were re-plastered and painted; electrical wiring was fixed; windows, ceiling and floors were repaired, and bathrooms constructed. A faculty room was built on the roof of the school, and the playground was repaired.

Many students who said they had lost interest in attending classes because of overcrowding and poorly maintained facilities expressed renewed vigor for learning once conditions in the school improved.

“Now we do not want to leave our school,” said Al-Amrani, who will soon graduate.“But we know that the next year’s students will be happy to study in our beautiful, new school.”

12/31/02: An earlier version of this story included an erroneous photo credit. Clinton Doggett took this photo.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.