A Southern Sudanese woman in Khartoum tells USAID staff she is eager to return to Bentiu, Unity state, April 14.

Christy Forster, USAID

A Southern Sudanese woman in Khartoum tells USAID staff she is eager to return to Bentiu, Unity state, April 14.

Christy Forster, USAID

A Southern Sudanese woman in Khartoum tells USAID staff she is eager to return to Bentiu, Unity state, April 14.

Christy Forster, USAID

A Southern Sudanese woman in Khartoum tells USAID staff she is eager to return to Bentiu, Unity state, April 14.

Christy Forster, USAID

In 2005, the Government of Sudan and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) ended nearly 22 years of civil war with the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA). But the peace that has held between northern and southern Sudan remains fragile.

Violence engulfed the disputed, resource-rich Abyei Area on the north-south border and the northern state of Southern Kordofan in the weeks ahead of South Sudan’s July 9 independence, raising fears of renewed north-south conflict. Internal strife also continues to affect large parts of both countries outside the state capitals, denying communities the security and development envisioned in the CPA.

Since 2005, USAID has been working with local government and civil society leaders to confront the country’s legacy of political conflict, violence, and instability. Through this conflict mitigation program, the Agency is working to counter threats to stability and seize opportunities to consolidate peace in South Sudan and along the volatile north-south border.

Mitigating Conflict along the Border

The “Three Areas”—Blue Nile and Southern Kordofan states and Abyei—are located along the political, ethnic, religious, and geographic fault lines of the civil war, and to this day are strategically important to the CPA’s signatories.

War-affected communities in these areas have been skeptical of peace, posing one of the greatest threats to its consolidation.

“The way we started,” explained Ken Spear, the head of USAID/Sudan’s Office of Transition and Conflict Mitigation in Khartoum, “was to identify local, reform-minded actors who, with just a few additional resources, would be able to make significant progress in addressing historical grievances in areas most prone to return to violent conflict.”

In 2006, USAID helped turn the tide away from renewed conflict in Blue Nile by empowering the state minister for health and Kurmuk County authorities to counter marginalization in the southernmost part of the state. The town of Kurmuk, in particular, was widely viewed as one of the border areas most likely to derail the peace process. The state government’s presence was nonexistent, signs of peace and development were absent, and communities were heavily armed and disillusioned by the outcome of the CPA.

USAID helped authorities extend essential services including health and education to Kurmuk and other underserved areas of southern Blue Nile. In 2010, USAID opened the Granville-Abbas Girls’ Secondary School in Kurmuk, which is named in honor of USAID employees John Granville and Abdelrahman Abbas Rahama, who were killed in Khartoum in 2008. The school is a model for girls’ education in the region. USAID-sponsored health training facilities in Kurmuk and Bau are helping to build a cadre of trained local health-care professionals.

“It is important that productive change agents are given credit for such transformations,” said Spear. “It strengthens their legitimacy, and that is what we want.”

Two Steps Forward, One Step Back

USAID’s achievements in helping mitigate conflict in the transitional areas have been matched by an array of challenges and setbacks.

Efforts to stabilize Abyei, including, for example, establishing an office complex for the nascent Abyei Area administration, have been frustrated by repeated outbreaks of violence in the area. Fierce fighting between forces loyal to the Government of Sudan and the SPLM recently forced the suspension of conflict-mitigation activities in much of Southern Kordofan and Abyei.

The violence here is of particular concern to pastoralist groups who rely on a cross-border existence, such as the Misseriya of Southern Kordofan. Without clear arrangements on the movement of goods and people across this new international boundary, the Misseriya fear they will lose access to essential grazing land and water in Abyei and South Sudan.

In response, USAID helped construct or rehabilitate 17 water yards—elevated water-storage reservoirs—along key migration corridors to reduce the Misseriya’s movement into South Sudan, and lessen the likelihood of resource-driven conflict. The Agency is now creating opportunities for the Misseriya to improve their livelihoods by involving youth in marketable activities, rehabilitating the meat and vegetable market in Muglad, and providing households with agricultural assistance such as training in the use of donkey plows, which can potentially double the amount of land a family is able to till.

Enhancing Community Security in South Sudan

Across the border in the new Republic of South Sudan, USAID launched a conflict-reduction initiative in 2009 following a worrisome spike in inter-ethnic conflict.

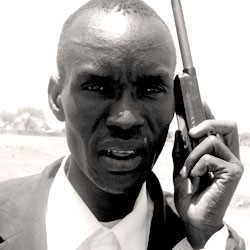

Through this effort, local government bodies are working to improve community security in some of South Sudan’s most remote and volatile areas such as Akobo, Pibor, Mayom, and Panyijar counties. U.S. aid helped the municipalities purchase highly visible office spaces and communication and transportation equipment, which in turn has enabled county and payam officials, as well as traditional authorities, to communicate and coordinate responses when there is tension or an outbreak of hostilities.

Peter Wol Akol, the administration officer/acting payam administrator for Jorbiooc/Malual West Payam, Aweil North County, in South Sudan's Northern Bahr el Ghazal state, on a USAID-sponsored satellite phone. In 2011, at least three potential conflicts were averted in conflict-prone states of South Sudan when local authorities learned about planned cattle raids and were able to thwart the attacks using USAID-funded communications equipment.

The change is striking.

“From a place like Panyijar, which can’t be accessed by road for about half the year, we’re suddenly getting e-mails from the county commissioner,” said Adam O’Brien, who was field program analyst for AECOM International, a USAID partner in the initiative.

In 2011, at least three potential conflicts were averted in Unity, Warrap, and Jonglei states when local authorities learned about planned cattle raids and were able to thwart the attacks using USAID-funded communications equipment.

Outlets for Youth

The initiative is also providing activities and training for youth who have witnessed few positive changes in their communities during their short lives. Many young people living in zones of high conflict remain caught in a culture of war, accustomed to cattle looting and banditry to earn money.

With USAID support, youth have received block-making training in Akobo and Pibor in Jonglei state, Nasir in Upper Nile state, Panyijar and Mayendit in Unity state, Tonj East in Warrap state, and Rumbek North in Lakes state. In addition to providing the youth with equipment to start their own businesses, they have been hired to produce blocks for USAID-funded infrastructure projects in the region.

South Sudan

In the wake of Sudan's transition from a country divided to two independent states, USAID/South Sudan has established an Office of Transition and Conflict Mitigation that will further enhance peace-building in South Sudan but also develop complementary programs with the USAID/Sudan office in Khartoum to tackle north-south border issues.

“The sense of pride is palpable,” O’Brien said. “When you visit a place like Akobo, the people say, ’We built this ourselves!’”

At a ceremony launching the refurbished Akobo County headquarters in October 2010, Commissioner Goi Jooyul Yol said, “[This] is not only a sign of stability, but a sign of hope for many youth who used their energy to mold blocks rather than engaging in cattle rustling.”

“We are really digging deep into our soil,” said one young man who worked on the project, “and building peace in Akobo now.”

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.