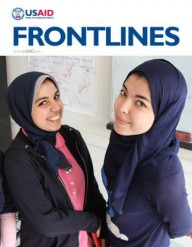

Left to right: Mona El Sayet, Hoda Mamdouh and Sara Ezat. Last year, these students from the Maadi STEM School for Girls competed in the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair in Los Angeles and placed third in their category.

Claudia Gilmore Gutierrez, USAID

Left to right: Mona El Sayet, Hoda Mamdouh and Sara Ezat. Last year, these students from the Maadi STEM School for Girls competed in the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair in Los Angeles and placed third in their category.

Claudia Gilmore Gutierrez, USAID

Left to right: Mona El Sayet, Hoda Mamdouh and Sara Ezat. Last year, these students from the Maadi STEM School for Girls competed in the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair in Los Angeles and placed third in their category.

Claudia Gilmore Gutierrez, USAID

Left to right: Mona El Sayet, Hoda Mamdouh and Sara Ezat. Last year, these students from the Maadi STEM School for Girls competed in the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair in Los Angeles and placed third in their category.

Claudia Gilmore Gutierrez, USAID

Meet Hoda Mamdouh. She’s a 17-year-old girl from the lush Nile Delta region of northern Egypt. Like most teenagers her age, she loves playing sports and listening to music. What makes Mamdouh different is her scientific research that’s taking her places she never imagined.

Last May, Mamdouh and two classmates traveled halfway around the world to compete in the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair in the United States. Together these high schoolers found a way to purify drinking water—from either taps or well—using 24 percent less energy than typically used in thermal water distillation. They won second place at Intel’s national science fair in Egypt. And at the global competition in Southern California, they placed third in their category among 1,600 of the best and brightest students in the world.

As high school juniors, Mamdouh and her friends are already preparing to become agents of change in Egypt. They attend the Maadi STEM School for Girls, one of two new secondary schools in Egypt that focus on science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Here they learn how to think outside the box, conduct experiments and work in teams—all important skills for growing into leaders and designing solutions to their country’s greatest development challenges. And they’re already putting them to use, conducting classroom research on issues directly related to Egypt’s economic growth like effective water use, traffic congestion and disease prevention.

“Coming here was a turning point in our lives,” Mamdouh says. “We went from memorizing every day at school to doing real research. Everyone’s a teacher, and everyone’s a student.”

This state-of-the-art model for public education was introduced to Egypt by USAID’s Hala ElSerafy, a senior education specialist at USAID’s mission in Egypt, and her team of experts. Instead of using your average high school curriculum—which in Egypt is rote memorization—these students become scientists in the classroom and learn from hands-on experiments and open dialogue.

USAID partnered with the Ministry of Education to build and develop the country’s first two STEM schools three years ago—one for boys and one for girls. “The idea is to raise a generation of critical thinkers and future leaders,” said Maadi school principal Samia Ahmed. “We believe our youth can solve Egypt’s grand challenges through science, technology, engineering and mathematics. And, so far, our experiment is working.”

Currently, 300 students attend the girls’ school and 357 students attend the boys’ school, both located in suburbs outside Cairo. Students from throughout Egypt are selected through their national test scores—the initial groups included only students scoring in the top 2 percent in the country. USAID is partnering with the Government of Egypt to expand this model of public education to all 27 governorates in the country.

Three new schools are nearly complete—two in the Nile Delta region and one in the southern governorate of Assuit—with plans to construct four more by 2017. All nine STEM schools will be able to enroll 3,600 students per year, giving Egypt’s brightest students the opportunity to think outside the box and perform real research before they even graduate high school.

“With the right teachers and education, our students here are capable of anything they set their minds to,” said ElSerafy. “For example, one STEM student, a 16-year-old boy, recently told me he wants to find a cure for Hepatitis C. He started his research at school and was invited to study with university faculty in Germany.”

To accomplish the aims of the project, USAID provided a grant to World Learning, which in turn partnered with three U.S.-based STIP institutions—The Franklin Institute, the Teaching Institute for Excellence in STEM, and the 21st Century Partnership for STEM Education— to help transform these STEM schools into incubators for future leaders and innovators who have the potential to advance research that fuels innovation and generates employment opportunities.

“USAID has a history of embracing and advancing science, technology and innovation to create new solutions for age-old challenges,” said Mary Ott, USAID deputy assistant administrator for the Middle East. “The projects the Egyptian STEM students are working on—ranging from water desalination to ultraviolet germicidal irradiation techniques—show the kind of innovation and brilliance that the world needs.”

Now others around the world are looking to Egypt’s model of STEM education and talking about ways to introduce it in their own countries. At a recent conference for Arab ministers of education, representatives from both Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates discussed plans to send their students to Egypt’s STEM schools for summer camp this year.

“This will be a great chance for youth from around the region to come and learn how STEM works,” said ElSerafy. “Egypt has really shown the world how this type of education can play a powerful role in development—and delegations around the Arab world are taking careful note.”

The Government of Egypt has also taken note of these remarkable students and their teachers. Just last September, Egyptian President Abdel ElSisi awarded STEM teachers and students with the Order of Distinction by presidential decree, the highest medal bestowed upon Egyptians who make significant contributions to society. Mamdouh and her two classmates who competed at the international science fair in the United States were among the students honored by President ElSisi. He later declared expanding STEM education one of his top educational priorities for Egypt.

Now Mamdouh’s planning her next steps after graduation. “I want to find a cure for Alzheimer’s disease,” she says. “My wish is to study at MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology] and research stem cells because I believe they hold the cure.”

Related Video

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.