Lead farmer John Mulnye explains the row spacing planting method to smallholder women farmers whom he mentors through a USAID project.

Lauren Bell, Peace Corps

Lead farmer John Mulnye explains the row spacing planting method to smallholder women farmers whom he mentors through a USAID project.

Lauren Bell, Peace Corps

Lead farmer John Mulnye explains the row spacing planting method to smallholder women farmers whom he mentors through a USAID project.

Lauren Bell, Peace Corps

Lead farmer John Mulnye explains the row spacing planting method to smallholder women farmers whom he mentors through a USAID project.

Lauren Bell, Peace Corps

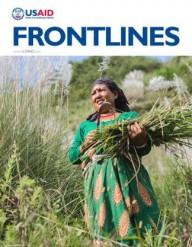

Victoria Asaaro is a role model for female farmers across the savannahs of Binaba, a small village in northern Ghana close to the Burkina Faso border. Asaaro is a successful maize farmer, mother of four, agricultural supplies merchant and leader of a 75-member women’s farming group. But just a few years ago she was a subsistence farmer struggling to make ends meet.

Farming is a tough business anywhere, but it is especially hard for farmers like Asaaro in northern Ghana.

Frequent droughts and floods diminish their yields, and many farmers rely on others to plow their fields for them, which can mean significant delays during the short planting season. Things started changing for Asaaro in 2011 when a USAID project taught her new ways to deal with climatic and economic shocks and turn her farming into a booming business.

“My women’s group and I learned how to manage our farms. Now we have our own plows and also a donkey cart to move produce to our houses,” she said. “Now we do not have to depend on others to plow for us. Others now depend on us for our plows.”

The Agricultural Development and Value Chain Enhancement (ADVANCE) project, part of the U.S. Government’s Feed the Future initiative, was what propelled Asaaro from subsistence farmer to commercial farmer.

ADVANCE, currently in its second phase, helps farmers like Asaaro access markets and inputs—such as seeds, fertilizers and equipment—and deal with an unpredictable climate and shifting economic conditions. Its first five-year phase helped 34,000 farmers in northern Ghana to more than double their yields and incomes. Its second phase, launched last year, aims to reach 100,000 additional farmers.

Northern Ghana has developed at a slower pace than the rest of the country. Due to its remote location, sparse population and limited resources, the northern region has not benefited from the investment and development occurring along the coastal regions of the country, where gold, cocoa, oil and ease of access to international markets exist. Most people in the north are farmers, but changing rainfall patterns and droughts threaten their livelihoods. Because of the climate there, farmers only get one growing season, while farmers in other regions of Ghana have two or three growing seasons.

In the regions where ADVANCE works, 90 percent of communities are prone to drought, 54 percent are vulnerable to bushfire and about a third are vulnerable to floods. As a result, most farmers are vulnerable to extreme poverty, hunger and malnutrition.

USAID gives these farmers the agricultural and financial tools and technologies to cope when shocks like these occur. The project works with the Ghana Agricultural Insurance Program to offer farmers climate-related insurance so they can recover their losses when catastrophe strikes, and works with banks to help them access credit. It also conducts research on drought-resistant and shorter-maturity crops, which enable farmers to have bountiful harvests even in the face of natural disasters.

The project trains farmers in the agricultural, marketing and business skills they need to improve their profits from farming. For example, USAID counsels farmers not to cut down shea trees on their fields since they are a critical natural resource and a valuable source of additional income for women, who can produce and sell shea butter. The project also trains farmers in conservation agriculture techniques such as minimum tillage, which boost yields while minimizing environmental and financial costs.

It’s All Business

Technology and the media have been central to outreach efforts. Farmers now receive text messages with up-to-the-minute, highly accurate weather forecasts and tips on everything from when to plant, harvest and spray their fields to how to best market their crops. There is also a radio and text message campaign against bush burning, a common practice that farmers use to clear their fields, which causes serious damage to farmlands and intensifies the impact of climate change.

Reaching farmers via multiple mediums has proven effective because more people have access to mobile phones than electricity in Ghana.

“For transformation to occur, it is necessary to adopt a commercial and competitive approach to agriculture,” explained Emmanuel Dormon, ADVANCE chief of party. One of the project’s aims is to create an entirely self-sustaining business model.

It does this by training, mentoring and dispensing technical advice to farmers like Assaro who are more progressive and commercially connected and own significant amounts of land and resources. These “nucleus farmers” then provide tractor services, improved seed, fertilizer, post-harvest services like shelling, and credit to smallholder farmers.

They also link smallholder farmers to larger markets throughout the country where they can sell their products, as well as markets where they can buy resources like low-cost, water-saving, nitrogen-based fertilizers—markets to which they would otherwise have no access.

This nucleus farmer model works because it is mutually beneficial for both nucleus farmers, who are paid in-kind for their services by smallholders after the harvest, and smallholder farmers, who gain the services, skills, technologies and access to markets needed to boost their incomes.

Asaaro has benefitted from this arrangement as both a smallholder farmer and a nucleus farmer. Due to her unique perspective, she takes special pride in mentoring other female farmers.

“The women in my group have learned to plow better, sow, fertilize and prepare their land. It affects their lives because now they save on inputs, get more yields and make bigger incomes,” she said.

While droughts, floods, bushfires and shifting economic tides continue to threaten her income, she is now confident that she has the skills to flourish no matter what comes her way. “I am very proud,” she said. “I am prepared. Now I know if something happens, I don’t have to lose everything.”

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.