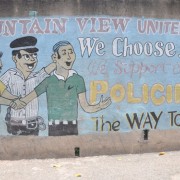

Students at the launching of Guatemala’s bachelor’s degree program in police science with a specialization in community-based policing.

Gabriela Lehnhoff, Violence Prevention Project

Students at the launching of Guatemala’s bachelor’s degree program in police science with a specialization in community-based policing.

Gabriela Lehnhoff, Violence Prevention Project

Students at the launching of Guatemala’s bachelor’s degree program in police science with a specialization in community-based policing.

Gabriela Lehnhoff, Violence Prevention Project

Students at the launching of Guatemala’s bachelor’s degree program in police science with a specialization in community-based policing.

Gabriela Lehnhoff, Violence Prevention Project

Flory Lemus had always wanted to be a cop. Ever since she was a teenager, the 26-year-old native of Guatemala City dreamed of wearing the same police uniform her father wore so proudly, and, in January 2007, she joined the police force.

Although Lemus initially encountered difficulties as a woman in a male-dominated environment, she soon gained a general sense of professional fulfillment despite being keenly aware that the institution required pressing changes.

For her, effective law enforcement is a necessary requirement in any society, especially in one as unequal and unjust as Guatemala’s. Lemus also believes that capacity building and specialized training is the right way to modernize and improve the effectiveness of the Guatemalan police force.

The police force that Lemus joined suffers from many institutional weaknesses and is hardly a credible institution in Guatemala. A comprehensive effort to correct the force’s deeply-rooted institutional shortcomings has been a long-standing challenge to consecutive national governments and donors like USAID.

Lemus is one of a select group of police officers who, with the support of the donor community in Guatemala, has benefited by visiting several countries to take a range of training courses—from crime prevention to community-based policing. She is also enrolled in the new USAID-supported undergraduate degree program in police science, which she believes will spawn a new mentality among her peers and the upper ranks of the institution.

The news reports about soaring violent crime in Central America have replaced the long-standing media focus on the internal armed conflict that ravaged the isthmus only a couple of decades ago. Indeed, in the last decade, the number of fatalities exceeds those reported during the conflict that bloodied the region in the 1980s and 1990s.

The public security crisis currently affecting the countries of the Northern Triangle—Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras—has made the readiness and capacities of their police forces an issue of heated public debate. And although everyone agrees on the need to modernize and reform the region’s police forces, efforts in that respect have been timid at best.

In Guatemala, the 1996 U.N.-brokered peace accords brought an end to its brutal 36-year civil conflict. The accords called for a clear separation between the police and the military and for the creation of a new police force to replace the old public security apparatus that had been complicit in human rights violations.

However, the new National Civilian Police (PNC) was composed mainly of members of the old force it replaced. The incoming members were rapidly incorporated without adequate training or background checks. According to some reports, five years after the signing of the peace accords, more than half of the PNC rank-and-file were members of the old security force.

The race against rapidly deteriorating citizen security also led to measures that further compromised the professionalization of the new force. Guatemalan authorities, for example, rushed cops out of the academy and onto the streets to pursue criminals. This led to serious deficiencies in recruitment, training, leadership and internal discipline.

The PNC’s reputation was furthered damaged by high-profile cases of police corruption and involvement in illicit activities. These included several allegations of extrajudicial killings and various drug-related offenses.

Encouraging Steps Toward Reform

Guatemalan President Otto Pérez Molina, who took office in January 2012, says public security is at the top of his priorities. The retired army general moved quickly to deploy troops to support police patrols in high-crime areas. This controversial measure continues to be a matter of heated public debate.

Pérez Molina announced his Pact for Security, Justice and Peace as the framework of his government’s efforts to combat crime, and he took steps to rekindle police reform efforts. Six months into his mandate, he issued an executive order to reform the structure and organization of the PNC.

The move effectively transformed prevention and community-based policing as core philosophies governing the work of the police. Soon after, the government launched the new officers’ school within the existing police academy. This new entity houses the academic, technical and managerial training programs for officers.

Last October, the Guatemalan public security hierarchy launched a new bachelor’s degree program in police sciences, with an emphasis on community-based policing. This program, supported by USAID’s Violence Prevention Project, is part of the new curricula developed for the officers’ school and is the first of its kind in the country’s history. The new degree is offered at the police academy in conjunction with Guatemala’s Western University. It gives officers the opportunity to acquire a university-level education in law enforcement through courses taught by experts and senior police officers that bring a wealth of theoretical and practical knowledge to students.

The 218 students currently enrolled in the one-year program are officers that had received previous university education. Financial assistance from the USAID project, approximately $700,000, was used to develop the program and to fund 147 scholarships benefitting officers who have been vetted for any human rights violations, per the U.S. Leahy Law.

During the launching ceremony in October 2012, USAID/Guatemala Mission Director Kevin Kelly stressed that “better educated police officers are very likely to become better performers.”

USAID/Guatemala’s new Security and Justice Sector Reform Project provides technical assistance and support for the country’s police and for the Police Reform Commission. It supports the development of a police career law in order to establish a merit-based career path system for the police, as well as a long-awaited police doctrine. It is also working to strengthen the PNC’s financial and management systems.

The U.S. Embassy’s Narcotics Affairs Section is addressing police corruption by working only with vetted units. Similarly, the U.N.-mandated International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala is aggressively working to stave off corruption among the PNC’s hierarchy.

Just before the end of 2012, the government announced a restructuring of the Ministry of Government. Chief among the changes implemented was the creation of a new Vice Ministry for Violence and Crime Prevention. The move supports a new institutional climate conducive to state-of-the-art approaches to fighting crime.

All of the measures and reforms represent a historic opportunity to modernize Guatemala’s PNC. Some of them even seem to echo Lemus’ convictions that a cultural transformation within the PNC towards prevention and better trained personnel will generate the necessary conditions to significantly improve the effectiveness of the country’s police force.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.