A nurse from the Maragusan Rural Health Unit, left, gets ready to visit patients in surrounding villages on a motorcycle taxi, which accommodates up to six passengers.

D. Golla, USAID

A nurse from the Maragusan Rural Health Unit, left, gets ready to visit patients in surrounding villages on a motorcycle taxi, which accommodates up to six passengers.

D. Golla, USAID

A nurse from the Maragusan Rural Health Unit, left, gets ready to visit patients in surrounding villages on a motorcycle taxi, which accommodates up to six passengers.

D. Golla, USAID

A nurse from the Maragusan Rural Health Unit, left, gets ready to visit patients in surrounding villages on a motorcycle taxi, which accommodates up to six passengers.

D. Golla, USAID

Jocelyn Canania is a health worker from a barangay (village) within New Bataan, a rural town in the Philippines’ southern region known as Mindanao. Forests cover half of New Bataan’s mountainous landmass, and, with a population of 50,000 people, the town is a large service hub for surrounding, less populous villages.

A doctor, nurse, medical technologist and handful of health workers comprise New Bataan’s Rural Health Unit, where people from near and far come to give birth, immunize their children, get treated for illnesses and attend to health needs that their villages are not equipped to meet.

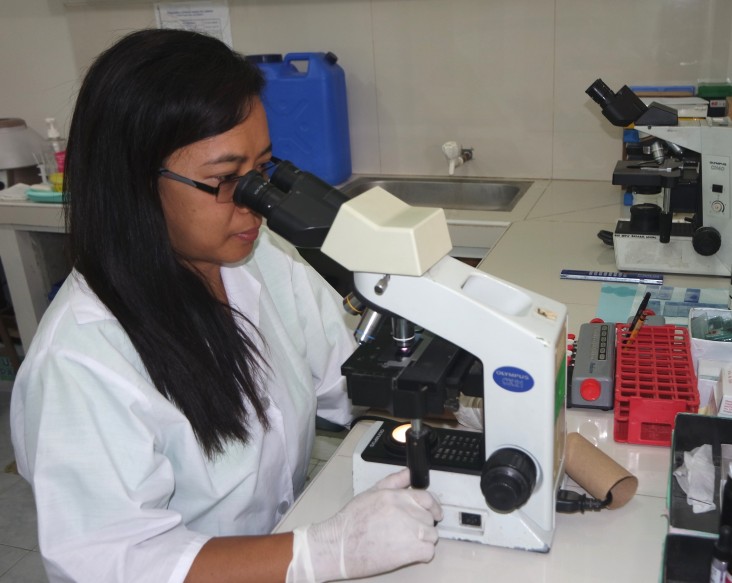

Canania spends most of her time at a neighboring village health station, treating basic health concerns. She reports weekly to the rural health unit, taking along slides that contain the sputum of patients believed to have tuberculosis (TB).

Nationwide, nearly 410,000 Filipinos, most of them in the economically productive age range of 15 to 64, contract TB every year, resulting in economic losses valued at $180.7 million. Patients must comply with at least six months of daily medications to be cured. This makes the disease even more difficult to overcome for those who live in geographically isolated and disadvantaged areas.

Across the country, rural communities cannot access basic care for critical health needs, including TB. Building upon its previous work to combat TB in the Philippines, USAID launched a five-year, $28-million project in 2012 that improves detection of the disease, thus preventing its spread. Implemented by the Philippine Business for Social Progress, the Innovations and Multisectoral Partnerships to Achieve Control of Tuberculosis project, or IMPACT, establishes tuberculosis remote smearing stations, allowing people to get tested near their homes for easier access to diagnosis and treatment, if needed.

Delivering Diagnoses

Health stations in remote villages offer scant services. But their structure and facilities—like ventilated rooms and running water—are enough for USAID to transform them into tuberculosis remote smearing stations.

Committed local governments provide supplies, such as glass slides and disinfectants. Meanwhile, USAID and its partners train health workers to collect sputum of people exhibiting TB symptoms. It is a critical step in diagnosing TB.

“Smearing” refers to the tedious process of preparing sputum for testing. Health workers like Canania spend hours carefully spreading samples on slides until the desired size and thickness is achieved. The risky procedure exposes them to the disease, so they are also trained in infection control.

Each week, slides are delivered to the nearest rural health unit for a medical technologist to stain and examine under a microscope. This is the primary method for diagnosing TB in low- and middle-income countries, where 98 percent of TB deaths occur.

“The tuberculosis remote smearing station is a simple innovation for detecting TB,” says Belfrando Cangao, chief of party of USAID’s IMPACT project. “It brings laboratory services directly to villages.”

Ultimately, the project diagnoses people who would otherwise go untested. Patients must wait one week for results, but the delay is better than not getting tested at all. The practice of using remote stations helps to cure more people and prevents the disease’s spread.

“I feel privileged to do this,” says Canania. “We are helping our community.”

The practice also alleviates burdens in rural health units. “It helps me with my workload,” says Gemma Mangco, medical technologist of the New Bataan Rural Health Unit. “I can now focus on reading slides and other tasks.” This facilitates quicker results and allows for immediate treatment. The Philippine Government provides free medication for TB patients.

Since 2013, USAID has installed 249 remote smearing stations throughout the country.

Dispelling Misperceptions and Urban Legends

Nestled along rivers and mountain ranges, the villages surrounding New Bataan are home to indigenous people, miners and farmers. Here, families earn around $90 a month.

As village health stations lack equipment and power, people must travel to a rural health unit to get checked for TB. But a one-way trip on a motorcycle taxi costs between $2 and $20, an unthinkable expense for most families. Some venture out to the twisty, rocky roads on foot, walking up to six hours. Most cannot afford time away from work or household duties. Instead, they resort to homemade herbal medicines, often getting sicker and spreading the disease to others.

And there are also the misperceptions and stigma that prevent people from getting TB care.

Estrellita Apale, 51, had to stop working as a manicurist near New Bataan when chronic backaches and weight loss debilitated her. Health workers urged her to get tested for TB. Apale resisted, saying it was impossible for her to have TB because she did not smoke or drink.

“I explained that TB is transmitted by air. Drinking and smoking do not cause it,” says Mangco.

Apale, in fact, did have TB. She underwent months of treatment and was declared cured in December 2015.

Melchora Gornes, another health worker from New Bataan, faced similar roadblocks when visiting the homes of people with prolonged coughing. “Some refused to give sputum samples,” Gornes said. “They said phlegm is dirty and should not be given to others.”

Mangco, Gornes and the other USAID partners dispel these misperceptions, assuring people that diagnosis and treatment help them and their community.

Arnel Torres, 24, is on his fourth month of TB medication and once held similar misperceptions. “People should not be ashamed,” he says. “It’s not their fault if they contract TB. What’s important is to get cured.”

Despite these challenges, the remote smearing stations have yielded good results. From January 2012 to June 2013, they detected 10 to 30 percent of new TB cases in the provinces of Pampanga, Laguna, Leyte and Compostela Valley. New Bataan is in Compostela Valley, where the project detected 15 percent of new TB cases.

USAID also helped the Philippine Department of Health draft an administrative order that expanded the remote smearing station concept to include urban communities. Informal laboratory workers in cities now smear slides, just as they do in remote villages.

So far, two regional health offices, one in Mindanao and another in Luzon, have replicated this concept without U.S. Government support.

The Last Hurdle

With these successes, USAID now addresses quality control. National standards state that provincial-level medical technologists should check the quality of smeared slides from TB microscopy laboratories, such as those in rural health units, quarterly. While this standard helps to ensure accurate diagnostics, some laboratories go years without quality checks due to transportation costs and limited staffing.

To address this, USAID gathered medical technologists from rural health units in Basilan, another region of Mindanao, to check one another’s work. They discussed their challenges and lessons learned. While this is not a perfect solution, it fosters learning and communication.

In Lanao Del Sur, also in Mindanao, the IMPACT project, together with the provincial and municipal health offices, monitors health workers as they disseminate information on TB prevention and control, and collect and smear sputum samples from suspected TB patients. This allows for quick diagnostics and instant feedback on the workers’ performance.

The project also is focusing on sustainability, ensuring that families can access lifesaving services long after U.S. support has ended. “This work shows that, with a committed government, an educated population and a dedicated cadre of health workers, rural and urban households can take their health into their own hands,” said USAID/Philippines Mission Director Susan Brems.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.