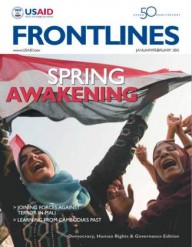

A volunteer provides literacy training to Malian youth.

Cassady Walters

A volunteer provides literacy training to Malian youth.

Cassady Walters

A volunteer provides literacy training to Malian youth.

Cassady Walters

A volunteer provides literacy training to Malian youth.

Cassady Walters

For two decades, Mali has enjoyed remarkable political stability characterized by four rounds of peaceful presidential and legislative elections and the proliferation of civil society organizations and private media outlets. In this sense, the country has been something of an anomaly in a sub-region where neighbors have been plagued by political repression and an absence of democratic freedoms.

Yet this democratic progress belies Mali’s record of development over the past 20 years. Indeed, 80 percent of the population continues to rely on subsistence farming or herding for their livelihood.

As a result, Mali remains one of the poorest countries in the world. Problems of extreme poverty are even greater in northern Mali where the Sahel covers most of the region, creating even harsher conditions for survival and greater underdevelopment.

To address this disparity, USAID works with the Government of Mali to engage local communities and improve basic service delivery in the northern regions through a wide range of activities that includes support to local health clinics, microfinance associations, youth employment programs, and decentralization activities. However, these collaborative efforts risk being undermined by a lawless environment that threatens the region.

Three distinct, yet occasionally intersecting sources of instability exist in northern Mali. The first is from persistent political and economic marginalization, most notably that of the Tuareg, an ethnic minority from the north that has not historically been well incorporated into the Malian state. Feeling the brunt of this marginalization, the Tuaregs have led several armed rebellions over the past 20 years.

In addition, tribal, ethnic, and clan-based divisions have been a constant source of instability, with hundreds of clans spread out over the north.

Lastly, the presence of the terrorist group al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, which has its roots in the Algerian Civil War, now poses a threat of violent extremism. While the recent kidnappings of foreigners and armed attacks have captured newspaper headlines, the group also represents a long-term destabilizing threat to the local population, especially youth who have limited opportunities for formal education or economic activities.

In 2005, USAID and the Departments of State and Defense joined an interagency counterterrorism effort to address the roots of terrorism in the Trans-Sahara Region. The Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership endeavors to bring to bear the tools of defense, diplomacy, and development in a strategically balanced manner to cut off support and safe havens for terrorist groups, while also strengthening partner nations’ capacities to meet their counterterrorism goals. This effort highlights the widely recognized assumption that counterterrorism efforts that neglect “soft side” inputs—such as basic efforts to strengthen community capacity—will not make a lasting contribution and might, in the end, do more harm than good.

The partnership is often cited as a good example of interagency coordination. By working with State and Defense, USAID has been able to identify areas of alignment, while still retaining the essential development and humanitarian character of its work.

One example of this collaboration is USAID/Mali’s work with the Department of Defense’s Civil Military Support Element (CMSE), which conducts routine humanitarian assistance missions in the north to support the Government of Mali’s stability operations in the region, but also works with interagency partners on counterterrorism and development efforts. For USAID/Mali, collaborating with the CMSE has been essential to monitoring programs in northern regions that require military accompaniment.

“We share many similar objectives with USAID in terms of increasing stability in the northern regions of Mali through humanitarian assistance and development projects,” says CMSE team member Dan Utley, who has accompanied USAID/Mali staff on trips to the north. “We also realize that security constraints make movement in the area difficult for non-military personnel, so we continue to support USAID with military aviation assets and other logistical planning.”

USAID works at the community level to address groups most vulnerable to extremist ideologies. Activities include youth empowerment through education, skill training, income generation, and advocacy. USAID also strengthens local governments’ capacity to manage local resources and provide peace dividends. In addition, the Agency improves access to information through community radio, and disseminates messages of peace and tolerance.

Many of these goals are achieved through the Support to Local Governance and Decentralization Program (PGP2), which provides training for elected officials and youth and female leaders of civil society organizations on conflict management mechanisms, peace-building activities, and natural-resource management as a way to reduce the risk of conflict and promote community cohesion. PGP2 also uses radio as a tool to deflect external destabilizing influences and build unity among community members. One way this is achieved is by training radio hosts to incorporate conflict resolution messages into programming.

USAID is working cross-sectorally in Mali to provide opportunities for youth and reduce their susceptibility to violent extremism. To address the mounting tension spurred by lack of opportunities for youth in the north, USAID’s governance, communications, education, and economic growth teams are supporting a project to put out-of-school youth, ages 14 to 25, to work and to use their new skills to benefit their communities.

The PAJE-Nieta (Support Project for Young Entrepreneurs) program imparts basic educational skills, such as reading and math, and identifies employment opportunities. Then, youth conduct a market analysis of their community to see if their expectations for work match the reality of the marketplace. Finally, after re-evaluating their goals, the participants enter a supervised apprenticeship in the field of their choice.

Under the project, education officers help train youth, building up their competencies, while the economic growth team provides the technical expertise for them to independently identify employment goals and market realities. Experts in governance and communications emphasize a civic engagement piece that focuses on leadership, conflict resolution, and training on the rights and responsibilities of citizens, particularly in relation to local communal governments.

Under the project, young people create associations within each village, which become the hub for all future vocational training and job mentoring. From this hub, youth design community service projects that they carry out in their own communities, showing their neighbors, their family, and their bosses that this program is more than simply receiving assistance, and that the youth of Mali are just as willing to give back as they are to move forward.

Scott Isbrandt, director of PAJE-Nieta, believes that this is the model of the future: “The future of our work should really revolve around cross-sectoral efforts,” he says. “It’s erroneous to think that an education project can succeed without a health piece, or an agriculture piece, or a democracy piece. It should all be cross-cutting. That’s what is exciting about this project for me, is that it really integrates all these components.”

PAJE-Nieta has been piloted in southern Mali with such success that President Amadou Toumani Toure publicly praised the project, claiming it would create 12,000 new jobs in the country—an exaggeration, but still, a potentially useful presidential endorsement.

With planning underway to expand to the north, now will be the time to see if this innovative solution, coupled with the ongoing work of the Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership, can begin the process of reconciliation, mediation, and pacification in the north of Mali.

As USAID/Mali Mission Director Rebecca Black observes: “It’s clear that engaging youth in our development activities is key to the success of all our programs, but in terms of the north, the need to create viable economic and civic opportunities for youth to reduce the threat of violent extremism is critical, and I’m hoping that PAJE can replicate the successes it’s had in the south.”

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.