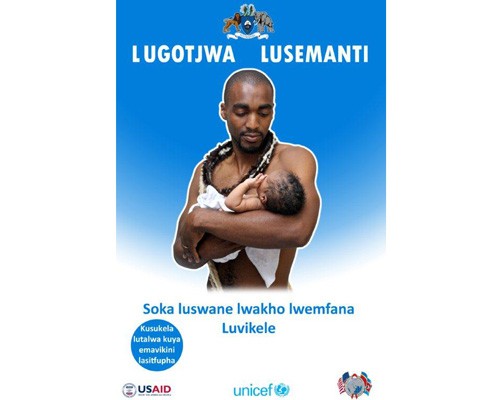

Image Poster from the USAID/PSI early infant male circumcision (EIMC) campaign in Swaziland.

Image Poster from the USAID/PSI early infant male circumcision (EIMC) campaign in Swaziland.

Image Poster from the USAID/PSI early infant male circumcision (EIMC) campaign in Swaziland.

Image Poster from the USAID/PSI early infant male circumcision (EIMC) campaign in Swaziland.

On June 26 of last year, Jabu Qwabe and Thokozani Mndzebele celebrated the birth of their new baby boy, Sihlelelwe, at a small hospital outside of Mankayane, Swaziland. Like all new parents, they immediately began to dream about their son’s future—where he would go to school, what he would study, what his career would be. Above all, they dreamed for him to live a healthy life—which is why, before leaving the hospital, they made the decision to have Sihlelelwe circumcised.

As parents of a child in Swaziland—the nation with the world’s highest adult HIV prevalence at 25.9 percent—their decision could very well save Sihlelelwe’s life. Voluntary medical male circumcision has been found to reduce the risk of sexual transmission of HIV from women to men by as much as 60 percent.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS, or UNAIDS, recommend voluntary adult circumcision in high HIV-prevalence countries like Swaziland to lessen the chance for HIV’s spread. They, along with UNICEF, also recommend early-infant male circumcision (EIMC) be implemented in parallel with adult circumcision programs. Health officials say that not only will infant circumcision help protect boys from HIV when they become sexually active later in life, but that it also protects infants and boys from serious health complications such as urinary tract infections and paraphimosis, a condition that can lead to pain and swelling in the affected area, and may require surgery. Three years ago, Swaziland’s Ministry of Health turned those recommendations into action and launched a nationwide program with assistance from the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through USAID, UNICEF, PSI and Jhpiego, a development organization affiliated with Johns Hopkins University.

In less than three years, the program has provided 1,300 voluntary circumcisions to boys across the tiny independent kingdom within the borders of South Africa. USAID’s support directly contributed to 1,226 of these procedures.

Infant circumcision is now offered for free in four health facilities in two of the four regions of the country, and coverage in each facility is about 25 percent of eligible baby boys. Three more facilities will begin providing EIMC in the first half of 2012, with more to be added during the latter half of the year. This network should service the entire country and the approximately 20,000 male infants born each year. The project is also training nurses to perform circumcisions—normally the purview of medical doctors only—to expand the number of infants offered the procedure.

“EIMC is a game-changing HIV intervention for Swaziland,” said Futhi Dlamini, EIMC coordinator for PSI/Swaziland. “It offers sustainability of services by being integrated in maternal and child health services. This program will be even more effective as parents become more accepting of EIMC and when nurses are allowed to perform the procedure.” Parents are introduced to EIMC at antenatal care clinics and child welfare clinics as well as the maternity units (including post-natal ward) of health facilities. They are approached by nurses, midwives and patient educators who are all trained on the basic facts of EIMC.

One parent must sign the consent form for the procedure, but mothers are often not comfortable giving consent without the father. Parents who agree to have their sons circumcised say they do so to prevent HIV in the future or because someone else in the family—typically the father—is also circumcised.

Parents who decline the procedure often say they will let their son decide for himself, that the baby is too young or that circumcision is not traditionally performed.

The Education Question

Swaziland is a traditionally non-circumcising country. Therefore, the introduction of early-infant male circumcision requires intensive community awareness and sensitization, training and buy-in of health care workers, and patience as the country begins to accept a new HIV intervention whose benefits become apparent in the long term.

To spread the word about the procedure to expectant parents and others in the country, USAID created the Lugotjwa Lusemanti campaign, which loosely translates to “bend the reed when it is green.” Through posters, brochures and media outlets, parents learned about the health benefits of circumcision and about why the ideal time for the procedure is soon after a boy is born, while he is still in a health facility.

The effort also recruited and trained volunteers to speak with expecting mothers, fathers and hospital staffers about infant circumcision. And, at Swaziland’s annual trade fair, the project hosted a special event called the “Baby Fair,” where mothers-to-be could attend a fashion show featuring pregnant models; visit stalls set up by local businesses selling baby-friendly products; and talk with peer educators about infant circumcision.

“I was scared of getting my baby circumcised, but after talking to some nurses, my boyfriend convinced me that it was the right decision to take and that it would benefit the child in the long term,” said Qwabe.

Qwabe and her boyfriend, who have since married, first heard about the campaign at the hospital when she went for check-ups. They found the procedure to be simple and quick and would now encourage their family members and friends to get their newborn baby boys circumcised early.

“The early-infant male circumcision (EIMC) project in Swaziland represents a real commitment by the government and the people of Swaziland to make a sustained effort in the push for an AIDS-free generation. Reaching infants at this critical stage reduces risk by completing the procedure before any sexual activity takes place, and results in fewer adverse effects for the individual,” said Emmanuel Njeuhmeli, senior biomedical prevention adviser in USAID’s Office of HIV/AIDS.

“We will not see an impact at population level in the next 15 years,” he continued, “but EIMC will allow us to maintain the impact that will be obtained with the adult voluntary medical male circumcision roll-out that is being supported by PEPFAR through USAID. The roll-out of EIMC in Swaziland also demonstrates that we observe a change in social norm in Swaziland that will have tremendous impact at population level, not just for HIV prevention, but also by averting other diseases.”

USAID has supported the roll-out of EIMC in Lesotho and Tanzania, with plans underway for Mozambique as well.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.