You're listening to a podcast by the U.S. Agency for International Development. I'm Kelly Ramundo.

Part 1: Grabbing for Land

Narrator: Imagine you're a farmer in Ethiopia or in Mozambique. You've been living and working on a small plot of land your entire life, but you don't really own it. At least not in the eyes of your government. So if it's not really your land, you may fear it being taken away from you. And it's happened, a lot, over the past few years as governments sold off millions of hectares to the highest bidders.

Theres a group of people, nestled in basement offices of the United States Agency for International Development, trying to change this. These experts say the seemingly simple act of helping landowners establish clear rights to their property – called Land Tenure – can have profound consequences.

And not just for smallholder farmers. But on the entire economies of developing countries. And for the international companies looking to invest in agriculture, a booming business these days, and a necessary one.

Gregory Myers is USAID's division chief for land tenure and property rights, and he recently helped broker the international adoption of a document called the Voluntary Guidelines for Land Tenure, a kind of best practices for resource governance. Meyers says guidelines aim to ensure that local people with customary rights to the land are less likely to be displaced and more likely to work with investors. To understand why the guidelines were the needed, Meyers says we've got to go back to the global financial crisis of 2007 and 2008.

Myers: In those years, when the market – the equity markets were bottoming and people were essentially looking for new investment opportunities, a lot of businesses around the world – private companies, sovereign wealth funds, et cetera – started to look for investments in hard assets, which would be land or agriculture and began to speculate, in 2007 and 2008, by trying to acquire, either through leases or by purchasing large tracts of land around the world, which has now become known as a land grab.

Narrator: So, in 2007, 2008, companies start to move around the world looking to acquire land. most of it in Africa . But that's not all that was happening.

Myers: Parallel to this, there is the global crunch around the food crisis and price speculation for food commodities. So it becomes almost a vicious circle with some countries looking for access to land and trying to acquire access to that land to meet their own food security needs. And that starts to drive up the price of land, which means that more speculators want to come in and try to acquire access to land And this is not a new phenomenon; it's a phenomenon that's been going on since time immemorial. But the size, the scale and the quickness with which all this took place was extraordinary.

Narrator: In 2010, the World Bank released its own study of the land-grab issue. That study estimated that countries, sovereign wealth funds, or companies had gobbled up 50 million hectares of land. Many NGOs say that the World Bank estimate is low, and that five times as much land may have been bought or leased – 250 million hectares. Myers says is impossible to know much land was taken. What we do know is that many people were displaced in the process. But how could this happen?

Myers: Because in most of these countries where these transactions have taken place, there are very weak or what we would even call dysfunctional property rights systems and, unfortunately in many of these countries, the state has articulated control or ownership over the land when in fact the state really doesn't own the land; actually the people who are on the land own the land. But the state doesn't – in many of these countries, doesn't recognize that ownership.

Narrator: Myers says that some were looking to make a profit with no regard for who owned the land. But other investors came to deals with good intentions. And then found themselves in a bind.

Myers: Because they go to a country like Ethiopia or Tanzania or Madagascar or Mozambique or Ghana, and they say, we would like to invest in agriculture and we would like to lease land, et cetera. And the government of that country says, yes, we own the land, and here's free land that you can invest in. They may not realize that they in fact are actually in a – in a – in a process of dispossessing people from their land rights.

Narrator: But that's not the only issue at play. We live on a hungry planet. Between 800 million and a billion people go to bed hungry every night. Clearly, he says we have to do something to promote agriculture. But that means there has to be investment in agriculture. So, while these investments in farmland – whether they're speculative or good investments or not, those investments are, to a certain extent, still very important, because the public sector doesn't have the money that it's going to require to be able to improve agricultural productivity to meet the needs of – the food security needs of the future.

Narrator: So, if you need the private sector to tackle the growing food needs of a growing population, the question becomes: do you bring responsible private sector investment into this equation?

Myers: The only way that's going to happen sustainably and in a way that's not going to lead to a lot of violence or conflict is that we're going to have to address the issue of property rights. So what we would do is, we would first try to find a way to secure the rights of the resources that people in these countries have, and then to find a way to link them to these private sector investors in ways that would be very profitable for those small holders.

Narrator: That strategy is at the heart of the U.S. Government's flagship food security program, called Feed the Future:

Myers: On one hand encouraging private sector and on the other hand supporting small-holder farmers. So while this issue around land-grabbing is highly controversial, it could also potentially be highly transformative, depending on the way in which it happens.

Part 2. The Guidelines

So the world needs agricultural investment to feed itself. And people have a right to their land. This, says Meyers, is where the voluntary guidelines come in to play. The guidelines were created by the U.N.'s Food and Agricultural Organization after two years of negotiations that started in 2008. They were written with input from civil society, farmers groups, the private sector and world governments. They were adopted in May by the U.N. Committee on World Food Security and the final product was hailed as a major milestone because land rights can be a highly charged and sensitive issue. So with the new guidelines in place, what comes next?

Myers: That's really the – that's really the most important question. The new frontier for us is really finding ways to implement the guidelines.

Narrator: As one example, the G-8, the group of 8 major industrialized nations, just launched something called the New Alliance For Food Security and Nutrition -- an effort to mobilize billions of dollars in private-sector investment in African agriculture. Land Tenure will a part of that.

Myers: There are six countries that we will focus on. And very quickly those countries could start the process of adopting. And the entry point for those countries would be to look at their policies and laws for land tenure and property rights; to look at modifying those laws to, one, recognize the rights that exist on the ground; and two, to look at their investment laws so that they can encourage private-sector investment in agriculture, but in a – in ways in which are most beneficial for small-holder producers, but at the same time which don't undermine the private-sector investment.

Narrator: Myers thinks the voluntary guidelines will have clear benefits for three parties: land owners, companies, and countries. A win-win-win, he says. Small farmers could benefit from the huge influxes of private sector investment in agriculture. They could organize, become shareholders, reap the benefits of the economic growth taking place in Africa for the first time. Companies would get to be good corporate citizens, and earn profits in way that respects human dignity. And countries, well, that's really two different entities, says Myers. The United States would benefit because if farmers starting growing enough feed their countries, we could reduce our food aid to these places, like the Horn of Africa. And the host countries would benefit because local populations would begin to contribute to their country's economic growth, by paying taxes, but not needing social safety nets.

In the end, everybody wins.

Part 3: The Human Face of Land Tenure

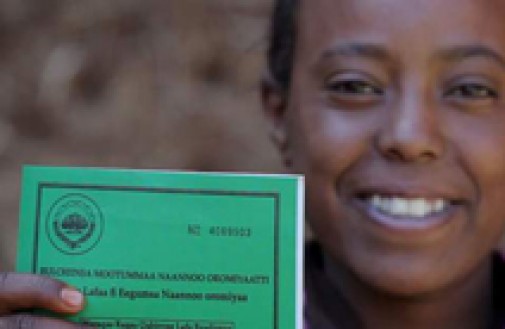

Let's go back to the smallholder farmers. The most vulnerable parties in this equation, and perhaps, the greatest beneficiaries. Meyers recently travelled to Ethiopia, where USAID has been implementing a land tenure program with the government for the last few years. He remembers one woman's story specifically. USAID, as part of the land tenure process, had recently helped mark the boundaries of her land. Unable to farm herself, she was leasing it out to a man, who told her the property measured just quarter of a hectare.

Myers: So after we did the certification, she realized that she actually had a hectare of land. And so afterwards she went back to the same man and she said, well, now you have to pay me four times the rent –– which he's now doing. So her household income went up by four times. And she said, as a result of that, she was able to buy more food for her children and – including sending kids to school that she hadn't been able to send to school before, including a daughter. So we thought, well, that's a remarkable story. And when we talked to other people who had received certificates, we started to hear similar stories about how now they had really much greater economic empowerment as a result of just having information about what they had rights to.

Narrator: Women are empowered in other ways as well:

Myers: And in Ethiopia, in one case in our early interviews, a woman came to us and said, I know my husband is having sex in town when he goes to the cities. And I am very worried that he's being exposed to AIDS. And I'm afraid that he'll bring it back to me and to our village. And so now that I have a land certificate, I can literally kick him out of the house and tell him, you know, I have my land, and I can feed myself and my children, and we're not dependent on you. And so if you choose to make those kinds of risky decisions, you know, you're on your own.

Narrator: While Africa is the epicenter of land tenure issues, USAID's work to ensure that people in developing countries acquire rights to their own property spans the globe. In East Timor. In the Philippines. And in African countries like Kenya, Liberia and South Sudan. Women and men are realizing the personal pride and the economic benefit that holding a land deed with their names on it can bring. Meyers sums it up well:

Myers: We have a motto down here in the land tenure division that says, “Changing the world one property right at a time.” And I think we all firmly believe that this is a fundamental building block of any democracy or market-based economy, if you don't have the right to property, you cannot be a member of the economy and you don't have a say in the political process. And I believe that as countries move forward toward recognizing or toward addressing this issue, which we call an enabling environment, eventually I think that this will reduce the kinds and the types of investments which we need to make in development, because people will have a greater political standing and greater economic opportunities to be able to do the kinds of things that you and I do here in the United States: to make our own individual decisions about how we best deem to manage our lives, how we want to engage in political decisions or political discourse, and how we want to engage in economic opportunities that will benefit ourselves and our families.

Narrator: So Myers and his team battle on in the basement of USAID, fighting land grab with guidelines, protecting rights and promoting investment. Changing the world one property right at a time.

For more on USAID's work in land tenure, check out the Agency's website under its environment and global climate change page.

Back Issues

- FrontLines July/August 2017

- FrontLines May/June 2017

- FrontLines March/April 2017

- FrontLines January/February 2017

- FrontLines November/December 2016

- FrontLines September/October 2016

- FrontLines July/August 2016

- FrontLines May/June 2016

- FrontLines March/April 2016

- FrontLines January/February 2016

- Resilience 2015

- Climate Change 2015

- Millennium Development Goals

- Science, Technology, Innovation and Partnerships

- Foreign Aid Impact in U.S. and Abroad

- Afghanistan

- Power/Trade Africa

- Grand Challenges for Development

- Maternal & Child Health

- The End of Extreme Poverty

- Energy/Infrastructure

- Depleting Resources

- Open Development/ Development & Defense

- Aid in Action: Delivering on Results

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.