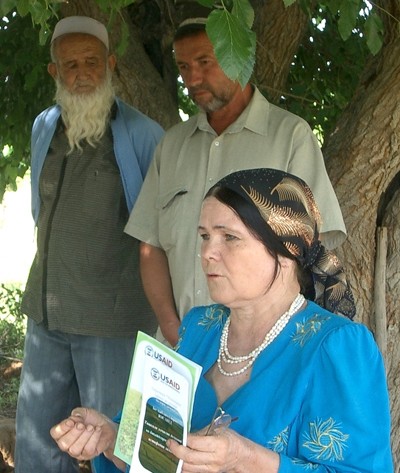

Gulbahor Rajabova (left), chairwoman of a farm, successfully defended her land rights in court with help from Director of Legal Aid Nodira Sidykova (right) and staff of a USAID-supported legal aid center in Spitamen, Tajikistan.

USAID

Gulbahor Rajabova (left), chairwoman of a farm, successfully defended her land rights in court with help from Director of Legal Aid Nodira Sidykova (right) and staff of a USAID-supported legal aid center in Spitamen, Tajikistan.

USAID

Gulbahor Rajabova (left), chairwoman of a farm, successfully defended her land rights in court with help from Director of Legal Aid Nodira Sidykova (right) and staff of a USAID-supported legal aid center in Spitamen, Tajikistan.

USAID

Gulbahor Rajabova (left), chairwoman of a farm, successfully defended her land rights in court with help from Director of Legal Aid Nodira Sidykova (right) and staff of a USAID-supported legal aid center in Spitamen, Tajikistan.

USAID

Gulbahor Rajabova never dreamed she would one day be a land activist in her rural home town in northern Tajikistan. But, when her farm was stolen out from under her by an influential businessman, she was left with no choice.

It happened five years ago as she was leading a 50-member farmers’ collective reorganized from a former Soviet Union cotton farm. One of the members used his business connections to persuade local authorities to assign half the land directly to him. The remaining 49 people, mostly women, were left with the least productive land and a $40,000 debt.

Rajabova knew this land transaction had taken place illegally, but she had nowhere to turn. She showed the fraudulent documents to local authorities, but they refused to take action.

As she was losing hope, she met lawyer Nodira Sidykova, the director of a USAID-supported legal aid center in Spitaman, Tajikistan, who agreed to take her case. They lost two appeals before reaching the Supreme Court and winning a favorable ruling. The court ordered the businessman to return the land to Rajabova and pay $17,000 towards the farm’s debt.

“We are teaching farmers about the law and to not be afraid to go to court and protect their interests under the law,” said Sidykova, who once aspired to become a judge but later realized she could make more of a difference focusing on land rights in her community.

Over the last three years, she has been part of a USAID-funded network of legal aid centers that have helped more than 100,000 farmers learn about and assert their rights. Through the support of one NGO in the network, “Rural Women,” the number of registered women-led family farms in four districts increased almost threefold, from 87 to 240. Many of these gains are being expanded through the U.S. Government’s flagship food security initiative, Feed the Future.

The program to improve farmers’ land rights put the brakes on what has become a sad rite of passage, particularly for female farmers. When farmers lack knowledge about their rights as workers on a collective farm, they are susceptible to exploitation. Farm members are paid in cotton stalks instead of cash, they don’t receive the maternity or sick leave benefits they are entitled to, and they face severe intimidation if they try to leave.

Without control over their land and without a source of income, these farmers are unable to grow enough nutritious food to feed their families. In fact, according to the USAID-funded 2012 Demographic Health Survey, 12 percent of children in Tajikistan are underweight, reflecting both acute and chronic under-nutrition; 10 percent of children are wasted--indicated by an acute, rapid weight loss and low weight for height; and 4 percent are severely wasted. Twenty-six percent of children under age 5 are stunted, of whom nearly half are severely stunted. As part of Feed the Future, farmers are learning how to break their dependency on unprofitable non-food crops such as cotton and support their families while growing nutritious food instead.

Breaking with Tradition

In Tajikistan, all land is owned by the government, but after the end of the Soviet Union, land-use rights were given to small-sized private collective farms. Individuals have the right to withdraw from the state or collective farm to establish private farms, but the process is not easy.

If a member of a farm wants to withdraw land and farm independently, they must get approval from the farm chairman, the district head official and the local land committee. He or she must also assume a portion of the debt accrued by the former state or collective farm—a debt that is often hundreds of dollars per hectare, especially in areas where cotton is grown, and in a country whose per capita GDP is only $2,200. Finally, the process, which also imposes additional informal costs, does not make it easy to determine the location, quality and size of the land plot assigned.

Twenty years after the Soviet Union’s collapse, Tajikistan’s economy remains heavily dependent on money sent back from men who leave the country for work. These remittances comprise just under half of GDP, making Tajikistan the most remittance-dependent country in the world.

Men are traditionally the head of the Tajik home. But even with up to 1 million of them living abroad, many women they have little ability to make decisions because that authority rests with the in-laws, or women are expected to make decisions only after consulting with husbands abroad. Their rights to the land they depend on for survival are tenuous.

“There are no legal impediments for citizens to obtain the right to use a plot of land,” says USAID agricultural expert Suhrob Tursunov. “However, in practice, members of collective farms, especially women, face numerous obstacles in withdrawing their land plots and registering their own farms.”

A nascent leasing market exists, but there are very few formal land transactions. Instead, the trade of land rights occurs on the black market. When the male head of household leaves the property, the women and families left behind are more vulnerable to violations of their land use rights.

Female farmers have banded together to stop this from happening. Rajabova now shares her experience with others and serves as a land-use activist in her community. “I can’t sit around and watch women being disrespected and mistreated because they don’t know their legal rights or are afraid to fight. I want to support them and help them get what they deserve,” she said.

With help from USAID through Feed the Future, women are supporting each other to overcome endemic corruption, a long legacy of government control over their agricultural choices, constant pressure to grow cotton, the continued existence of large and inefficient collective-style farms, and the lack of clear land use rights.

In three years, 62 land activists throughout Tajikistan received training from 10 legal aid centers, and are using their skills to educate their peers. When problems emerge, these land activists provide direct mediation and refer the case to a legal aid lawyer if it can’t be resolved outside of a lawsuit.

Additionally, the USAID-sponsored legal aid attorneys provided over 26,000 individual field and office consultations to farmers and successfully argued and won 49 major land use disputes in court during the three years of this project, which has recently concluded its work.

Worldwide, experts say there are clear benefits to societies that improve land rights.

“When women have more rights to land, there are cascading benefits for food security and poverty [reduction]. We have seen this firsthand in Tajikistan,” says USAID Mission Director Anne Aarnes. “When women gain freedom to farm, they grow healthier food for their families. They plant crops that last more than one season because they have faith that the land will still be theirs when the crops mature. It is inspiring to talk to women who went from not earning any money to being able to earn enough to send their children to university and to bring their sons home from migrant work abroad.”

Adds USAID Deputy Administrator Donald Steinberg: “Women’s access to land tenure, inheritance laws, to control what happens in agriculture sectors is key to development. If we could simply give women the same access to land, technologies and capital for farming that men have, we’d increase world food production by 30 percent. That means 150 million people would have access to food.”

Freedom of Choice

Helping farmers create their own independent farms ends their dependence on hierarchical cotton farms and allows them to grow more profitable high-yield vegetables instead. For years, the 28 members of the Abdurakhim Sarkor collective farm in Sughd, Tajikistan, worked long days growing cotton. Their annual salaries from the farm director never exceeded $250 per member. Though they wanted to start their own farms, they didn’t know where to begin.

That all changed when the NGO Saodat learned about their plight during a focus group held as part of a USAID project.

“The members of the farm didn’t know about their rights and obligations, especially how to create an independent farm,” said the NGO’s land reform lawyer, Mukarram Rasulova. “We walked them through the process step by step and provided the farmers with the help and documents necessary to create individual farms. Now, these farmers are enjoying the full freedom of choice over what to grow on their land, how to manage their crops, and when and how to disburse their revenues.”

USAID helped more than 700 women establish their own independent family farms as part of the land reform project. These women have achieved financial independence while being able to provide healthy food choices to their communities. The work has also led to changes across the country.

Last August, USAID helped the Government of Tajikistan draft a set of amendments to the land code that strengthen the security of land use rights and introduce the concept of the right to buy, sell, mortgage and transfer rights to land.

“A formal market framework, with secure tenure rights that are properly registered with the government, will provide the incentives needed to maximize the short- and long-term potential of the land. This is critical to achieving the economic development of Tajikistan’s agriculture sector,” says USAID/Tajikistan Country Director Katie McDonald.

Over the next five years, it is expected that over 200,000 Tajik women, children and other family members will receive targeted assistance from USAID to escape poverty and undernutrition through Feed the Future.

“Women are gaining more than a piece of land. They are gaining peace of mind as they have more freedom to grow food for their families and neighbors,” says Aarnes. “The conversion from cotton to control over farming choices has transformed lives. We’ve planted the seeds of land ownership, and now we are watching them blossom into healthy and stable communities.”

Adolat Means Justice

Adolat Khasanova is another Tajik with a land-use win. For 30 years, she worked 12-hour days without pay on a cotton farm. She sold milk and eggs from her cow and chickens to survive. When she decided to start her own farm, the town council chairman threw away her papers and told her to go away. This inspired her to fight.

“I’m a woman and a mother, and he mistreated me and disrespected me. I had to prove that I can achieve success,” she said.

A USAID-sponsored NGO in Khatlon assisted Khasanova throughout the process of starting her own farm where she now grows melons, eggplant and corn. She was eventually successful, and the 16 members of her new cooperative were free to grow whatever they wanted. However, her former boss on the cotton farm resented her success and cut off her irrigation water. Khasanova returned to the NGO for assistance. Through swift mediation from the legal aid center, her water was turned back on and she has not had problems since.

“I want to thank the American people for their support and for teaching women in these villages about their rights,” said Khasanova, whose first name, Adolat, means justice. She has made enough money to buy a car and to send her son to university.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.