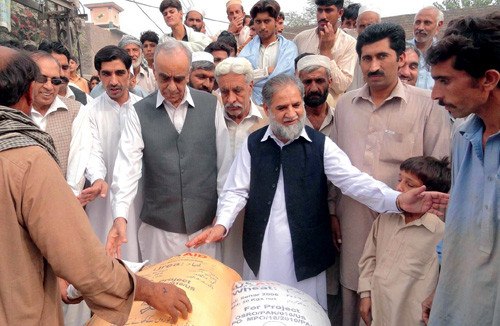

Punjabi farmers return home after receiving 50-kilogram sacks of wheat seed, fertilizer, and vegetable seed as part of USAID's $62 million post-flood wheat distribution program.

M. Ghani Khan/USAID

Punjabi farmers return home after receiving 50-kilogram sacks of wheat seed, fertilizer, and vegetable seed as part of USAID's $62 million post-flood wheat distribution program.

M. Ghani Khan/USAID

Punjabi farmers return home after receiving 50-kilogram sacks of wheat seed, fertilizer, and vegetable seed as part of USAID's $62 million post-flood wheat distribution program.

M. Ghani Khan/USAID

Punjabi farmers return home after receiving 50-kilogram sacks of wheat seed, fertilizer, and vegetable seed as part of USAID's $62 million post-flood wheat distribution program.

M. Ghani Khan/USAID

ISLAMABAD, Pakistan—On Sept. 30, a fifth of Pakistan was inundated with water and USAID was focused on flood relief. But there was other pressing business with the country that just couldn't be put off.

After a year of rising expectations, USAID finally signed a bilateral agreement committing the Agency to most of a $1.06 billion budget for fiscal year 2010—the first funding for the Pakistan aid bill that has become known worldwide as Kerry-Lugar-Berman, or KLB.*

The agreement cemented a reinvigorated U.S.-Pakistan partnership that has most prominently taken the form of strategic dialogue sessions in Islamabad and Washington.

USAID has a long history with Pakistan, and has provided over $4.5 billion in assistance since 2002. But in 2010, the mission found itself in the throes of major growing pains. The budget had jumped from $400 million in fiscal year 2008 to $1.1 billion in fiscal year 2009. Then the flooding put an entire year of planning and implementation into question.

Today, the water has largely receded. And with the help of USAID and other international donors, the displaced received shelter and food, and epidemics were kept at bay.

Ironically, the water that inundated so much agricultural land left the fields rich in nutrients and primed for an excellent harvest if only seeds for the winter wheat crop could be planted.

In response, USAID took about $62 million, mostly from KLB and augmented by funds from the Agency's Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance, to furnish wheat seeds via the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization to the hardest hit provinces. The effort started in the north, where the water had receded and winter would arrive first, with a $21 million program in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. That was followed by $25 million to implement the program in Punjab and $16 million in Balochistan.

All the while, USAID continues to work closely with the Pakistani government to ensure activities reflect mutual priorities, and are responsive to the most urgent needs, while building government capacity to pursue economic and political reforms with the help of international contractors and local institutions.

"Providing services in place of government institutions does little to help it provide the services after the programs close," said Acting Mission Director Denise A. Herbol. "Building capacity into governmental institutions helps them sustain delivery."

The approach echoes President Barack Obama, who in September 2010 signed a directive on development policy committing the United States to "invest in systemic solutions for service delivery, public administration, and other government functions where capacity exists. Public sector capacity and sustainability will be a core focus to the U.S. approach to humanitarian assistance."

Teaching someone to fish so they can feed themselves for a lifetime rather than giving them a fish so they can eat for a day, as the old saying goes, is a huge challenge given the public perception that such a large infusion of money should have an immediate positive effect on the quality of life for Pakistanis. That challenge is compounded by concern from American and Pakistani publics that the money be responsibly spent.

"We are excited about doing development another way," Herbol said. "But the reality is a lengthy process of helping the government put systems into place whereby they can effectively deliver meaningful public services in an effective, transparent, and accountable manner."

The Agency's mission in Pakistan must have a clear understanding of the existing capacity of federal agencies and provincial governments to account for funds they receive.

To that end, USAID is conducting extensive pre-award assessments for dozens of Pakistani governmental and civil institutions, and launching programs to help them build capacity and monitor the funded initiatives.

USAID has conducted more than 100 pre-assessment surveys of government agencies to identify deficiencies in accounting for funding, and in some cases, embedding accountants on-site. If deficiencies are identified, the assessments provide recommendations for how the institutions, whether they receive USAID funding or not, can improve their accounting and transparency mechanisms. An overarching monitoring and evaluation program is also about to be put in place.

"As stewards of the American taxpayers' money, the mission must not measure success by how fast the money moves but by ensuring it's moving in the right direction, getting to where it needs to be, and not getting lost," said Herbol.

The democracy and governance program, for example, is channeling nearly 80 percent of its portfolio through governmental or local organizations, including a program to provide services like clean water, drainage, and solid waste management to communities in all four provinces and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas; three small grants programs that focus on women's rights and other community-based initiatives; and an anti-corruption initiative designed to expose any corruption in KLB funding.

In education, USAID's work with the provincial government of Punjab expands on an existing "missing facilities" program being carried out with the World Bank, and will include $10 million for the reconstruction and resupply of flood-affected schools. Outside experts will train head teachers and district education office personnel.

USAID is also working directly with the Provincial Reconstruction, Rehabilitation, and Resettlement Authority (PaRRSA), a governmental body formed after large swathes of the Malakand Division were destroyed as security forces drove militants from the Swat Valley in the summer of 2009. Through PaRRSA, the $36 million program has begun work on 44 of a planned 112 schools damaged by the conflict. For the first time, schools will be built to three standard blueprints, according to school size.

Energy projects announced last year continue to move forward with rehabilitating key dams that provide power to the national grid; upgrading 11,000 inefficient tube wells used for irrigation; improving performance of the largest electric distribution companies; and harnessing the power of the wind for a clean, alternative energy source.

In South Waziristan, USAID is working with the governmental Frontier Works Organization, the Water and Power Development Authority, and other local agencies to rebuild roads, develop water infrastructure, and improve power systems. USAID projects are implemented through the local governing body, known as the FATA Secretariat, to enhance and solidify its authority with the populace in the tribal areas. In mid-November, 30 out of a planned 81 kilometers of road were complete.

Much work, however, remains as the long-term social and economic effects of the flood become apparent. Painstakingly developed plans that once seemed appropriate have given way to a harsher reality faced by millions of Pakistanis. But flood or no flood, the U.S. goal is to partner with the federal, provincial, and municipal governments and support their efforts to provide Pakistani people with better services and a better quality of life.

"Helping Pakistan become a more economically vibrant country is ultimately in the best interests of the United States," Herbol said. "Improving opportunity diminishes the appeal of extremism."

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.